On March 20, 1963, former major league infielder turned actor, Johnny Berardino announced his new role as internist Dr. Steve Hardy in the soon-to-debut soap opera General Hospital.

It was a role Berardino would continue to play for 33 years and over 4,300 episodes. Along the way, Dr. Hardy became the hospital's chief of staff while John himself dropped the second "r" from his surname ("Beradino") and gained a star on Hollywood's Walk of Fame. Berardino even convinced the soap's producers to cast friend Yogi Berra as a brain surgeon in one episode (though they refused to give the Hall of Fame catcher any spoken lines).

Acting was nothing new for the former member of the Browns, Indians, and Pirates. Berardino graced the silver screen as an extra in several Hal Roach "Our Gang" comedies at the age of six. He later played bit parts in movies such as Marty and North by Northwest. The majority of his thespian work, however, came via television, where the Los Angeles native made literally scores of appearances, usually playing the heavy on episodes of Dragnet, The Adventures of Superman, and countless other small-screen series.

Though just a .249 career major-league hitter, Berardino made an impact in the game. Browns teammate Al Zarilla tells of Berardino amusing the club with skits and Shakespearean dramas and soliloquies. While with Cleveland, owner Bill Veeck, always looking for a new promotion, insured the handsome infielder's facial features for a million dollars. Also, on May 15, 1946, Berardino's seventh-inning grand slam off New York Yankees ace reliever Johnny Murphy was a blow the Bombers never recovered from that season.

Courtesy of the Baseball Hall of Fame website: baseballhalloffame.org

Wednesday, March 23, 2005

Tuesday, March 22, 2005

Negro League History 101 - Part 2 of 2

Negro League History 101

Courtesy of negroleaguehistory.com

(Part 2 of 2 Parts)

3. The Golden Years Of Black Baseball

When Gus Greenlee organized the new Negro National League in 1933 it was his firm intention to field the most powerful baseball team in America. He may well have achieved his goal. In 1935 his Pittsburgh Crawfords lineup showcased the talents of no fewer than five future Hall-Of-Famers: Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell, Judy Johnson and Oscar Charleston.

While the Crawfords were, undoubtedly, black baseball's premier team during the mid-1930s, by the end of the decade Cumberland Posey's Homestead Grays had wrested the title from the Crawfords, winning 9 consecutive Negro National League titles from the late 1930s through the mid-1940s. Featuring former Crawfords stars Gibson and Bell, the Grays augmented their lineup with Hall-Of-Fame talent such as that of power-hitting first baseman Buck Leonard.

Contributing greatly to the ever-growing national popularity of Negro League baseball during the 1930s and 1940s was the East-West All-Star game played annually at Chicago's Comiskey Park. Originally conceived as a promotional tool by Gus Greenlee in 1933, the game quickly became black baseball's most popular attraction and biggest moneymaker. From the first game forward the East-West classic regularly packed Comiskey Park while showcasing the Negro League's finest talent.

As World War II came to a close and the demands for social justice swelled throughout the country, many felt that it could not be long until baseball's color barrier would come crashing down. Not only had African-Americans proven themselves on the battlefield and seized an indisputable moral claim to an equal share in American life, the stars of the black baseball had proven their skills in venues like the East-West Classic and countless exhibition games against major league stars. The time for integration had come.

4. The Color Barrier Is Broken

Baseball's color barrier cracked on April 18, 1946 when Jackie Robinson, signed to the Dodgers organization by owner Branch Rickey, made his first appearance with the Montreal Royals in the International League. After a single season with Montreal, Robinson joined the parent club and helped propel the Dodgers to a National League pennant. Along the way he also earned National League Rookie Of The Year honors.

Robinson's success opened the floodgates for a steady stream of black players into organized baseball. Robinson was shortly joined in Brooklyn by Negro League stars Roy Campanella, Joe Black and Don Newcombe, and Larry Doby became the American League's first black star with the Cleveland Indians. By 1952 there were 150 black players in organized baseball, and the "cream of the crop" had been lured from Negro League rosters to the integrated minors and majors.

During the four years immediately following Robinson's debut with the Dodgers virtually all of the Negro Leagues' best talent had either left the league for opportunities with integrated teams or had grown too old to attract the attention of major league scouts. With this sudden and dramatic departure of talent black team owners witnessed a financially devastating decline in attendance at Negro League games. The attention of black fans had forever turned to the integrated major leagues, and the handwriting was on the wall for the Negro Leagues. The Negro National League disbanded after the 1949 season, never to return.

After a long and successful run black baseball's senior circuit was no longer a viable commercial enterprise. Though the Negro American League continued on throughout the 1950s, it had lost the bulk of its talent and virtually all of its fan appeal. After a decade of operating as a shadow of its former self, the league closed its doors for good in 1962.

5. Only The Beginning Of The Story...

This brief narrative only capsulizes the story of Negro League baseball. Delving further into this fascinating era in American sports will reveal a rich and colorful story, which had profound impact not only on our national pastime, but also upon America's social and moral development. It is a story you won't want to miss!

Courtesy of negroleaguehistory.com

(Part 2 of 2 Parts)

3. The Golden Years Of Black Baseball

When Gus Greenlee organized the new Negro National League in 1933 it was his firm intention to field the most powerful baseball team in America. He may well have achieved his goal. In 1935 his Pittsburgh Crawfords lineup showcased the talents of no fewer than five future Hall-Of-Famers: Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell, Judy Johnson and Oscar Charleston.

While the Crawfords were, undoubtedly, black baseball's premier team during the mid-1930s, by the end of the decade Cumberland Posey's Homestead Grays had wrested the title from the Crawfords, winning 9 consecutive Negro National League titles from the late 1930s through the mid-1940s. Featuring former Crawfords stars Gibson and Bell, the Grays augmented their lineup with Hall-Of-Fame talent such as that of power-hitting first baseman Buck Leonard.

Contributing greatly to the ever-growing national popularity of Negro League baseball during the 1930s and 1940s was the East-West All-Star game played annually at Chicago's Comiskey Park. Originally conceived as a promotional tool by Gus Greenlee in 1933, the game quickly became black baseball's most popular attraction and biggest moneymaker. From the first game forward the East-West classic regularly packed Comiskey Park while showcasing the Negro League's finest talent.

As World War II came to a close and the demands for social justice swelled throughout the country, many felt that it could not be long until baseball's color barrier would come crashing down. Not only had African-Americans proven themselves on the battlefield and seized an indisputable moral claim to an equal share in American life, the stars of the black baseball had proven their skills in venues like the East-West Classic and countless exhibition games against major league stars. The time for integration had come.

4. The Color Barrier Is Broken

Baseball's color barrier cracked on April 18, 1946 when Jackie Robinson, signed to the Dodgers organization by owner Branch Rickey, made his first appearance with the Montreal Royals in the International League. After a single season with Montreal, Robinson joined the parent club and helped propel the Dodgers to a National League pennant. Along the way he also earned National League Rookie Of The Year honors.

Robinson's success opened the floodgates for a steady stream of black players into organized baseball. Robinson was shortly joined in Brooklyn by Negro League stars Roy Campanella, Joe Black and Don Newcombe, and Larry Doby became the American League's first black star with the Cleveland Indians. By 1952 there were 150 black players in organized baseball, and the "cream of the crop" had been lured from Negro League rosters to the integrated minors and majors.

During the four years immediately following Robinson's debut with the Dodgers virtually all of the Negro Leagues' best talent had either left the league for opportunities with integrated teams or had grown too old to attract the attention of major league scouts. With this sudden and dramatic departure of talent black team owners witnessed a financially devastating decline in attendance at Negro League games. The attention of black fans had forever turned to the integrated major leagues, and the handwriting was on the wall for the Negro Leagues. The Negro National League disbanded after the 1949 season, never to return.

After a long and successful run black baseball's senior circuit was no longer a viable commercial enterprise. Though the Negro American League continued on throughout the 1950s, it had lost the bulk of its talent and virtually all of its fan appeal. After a decade of operating as a shadow of its former self, the league closed its doors for good in 1962.

5. Only The Beginning Of The Story...

This brief narrative only capsulizes the story of Negro League baseball. Delving further into this fascinating era in American sports will reveal a rich and colorful story, which had profound impact not only on our national pastime, but also upon America's social and moral development. It is a story you won't want to miss!

Negro League History 101 - Part 1 of 2

Courtesy of negroleaguebaseball.com

(Part 1 of 2 Parts)

Most everyone knows that Jackie Robinson was the first African-American to play major league baseball during the modern era. Surprisingly, few people have given much thought to how Robinson came to the attention of major league scouts, where he played before signing with the Dodgers, or just what the nature of baseball in the black community might have been before professional baseball's integration.

In the following paragraphs we'll take a quick trip through the years of baseball in black America that led up to Robinson's 1947 debut in Brooklyn. Our tour is intended to introduce those who are just learning about the Negro Leagues to this fascinating era in the history of American sports and society. There won't be much here to interest the baseball aficionado -- just a brief introduction for those newly discovering Negro League baseball.

1. The Baseball World Before 1890.

While it would be quite a stretch to say that professional baseball in the North was integrated between the end of the Civil War and 1890, quite a number of African-Americans played alongside white athletes on minor league and major league teams during the period. Although the original National Association of Base Ball Players, formed in 1867, had banned black athletes, by the late 1870s several African-American players were active on the rosters of white, minor league teams. Most of these players fell victim to regional prejudices and an unofficial color ban after brief stays with white teams, but some notable exceptions built long and solid careers in white professional baseball.

In 1884 the Stillwater, Minnesota club in the Northwestern league signed John W. "Bud" Fowler, an African-American with more than a decade's experience as an itinerate, professional player. Fowler, a second-baseman by preference, played virtually every position on the field for Stillwater, enhancing the reputation that had brought him to the attention of white team owners. Fowler's baseball career continued through the end of the 19th Century, much of it spent on the rosters of minor league clubs in organized baseball.

In 1883 former Oberlin College star Moses "Fleetwood" Walker began his professional career with Toledo in the Northwestern League. A more than average hitter, Walker was among baseball's finest catchers almost from the beginning of his career. When the Toledo club joined the American Association in 1884 Walker became the first black player to play with a major league franchise.

In 1886 both Walker and Fowler were in the white minor leagues along with two other black stars, George Stovey and Frank Grant. Doubtless, many other black players were playing with teams in the "outlaw" leagues and independent barnstorming clubs. At least in the North and Midwest the best black players found a measure of tolerance, if not acceptance, in white baseball until the end of the 1880s. But in 1890 this situation abruptly changed.

As the season of 1890 began there were no black players in the International League, the most prestigious of the minor league circuits. Without making a formal announcement, a gentlemen's agreement had been made which would bar black players from participation for the next fifty-five years. Though black players continued to find work in lesser leagues for a time, within only a few short years no team in organized baseball would accept black players. By the turn of the century the color barrier was firmly in place.

2. Professional Black Baseball Comes To The Fore

While Fowler, Walker, Grant and others were working to find a spot (and keep it) in organized baseball, other black players were pursuing careers with the more than 200 all-black independent teams that performed throughout the country from the early 1880s forward. Eastern teams like the powerful Cuban Giants, Cuban X Giants and Harrisburg Giants played both independently and in loosely organized leagues through the end of the century, and in the early 1900s professional black baseball began to blossom throughout America's heartland and even in the South.

The early years of the 20th Century saw an emergence of several powerful black clubs in the Midwest. Teams like the Chicago Giants, Indianapolis ABCs, St. Louis Giants and Kansas City Monarchs rose to prominence and presented a legitimate challenge to the claim of diamond supremacy made by Eastern clubs like the Lincoln Giants in New York, Brooklyn Royal Giants, Cuban Stars and Homestead (Pa.) Grays. In the South, black baseball was flourishing in Birmingham's industrial leagues, and teams like the Nashville Standard Giants and Birmingham Black Barons were establishing solid regional reputations.

By the end of World War I black baseball had become, perhaps, the number one entertainment attraction for urban black populations throughout the country. It was at that time that Andrew "Rube" Foster, owner of the Chicago American Giants and black baseball's most influential personality, determined that the time had arrived for a truly organized and stable Negro league. Under Foster's leadership in 1920 the Negro National League was born in Kansas City, fielding eight teams: Chicago American Giants, Chicago Giants, Cuban Stars, Dayton Marcos, Detroit Stars, Indianapolis ABCs, Kansas City Monarchs and St. Louis Giants.

In the same year Thomas T. Wilson, owner of the Nashville Elite Giants, organized the Negro Southern League with teams in Nashville, Atlanta, Birmingham, Memphis, Montgomery and New Orleans. Only three years later the Eastern Colored League was formed in 1923 featuring the Hilldale Club, Cuban Stars (East), Brooklyn Royal Giants, Bacharach Giants, Lincoln Giants and Baltimore Black Sox.

The Negro National League continued on a sound footing for most of the 1920s, ultimately succumbing to the financial pressures of the Great Depression and dissolving after the 1931 season. The second Negro National League, organized by Pittsburgh bar owner Gus Greenlee, quickly took up where Foster's league left off and became the dominant force in black baseball from 1933 through 1949. The Negro Southern League was in continuous operation from 1920 through the 1940s and held the position as black baseball's only operating major circuit for the 1931 season. In 1937 the Negro American League was launched, bringing into its fold the best clubs in the South and Midwest, and stood as the opposing circuit to Greenlee's Negro National League until the latter league disbanded after the 1949 season.

Despite the difficult economic challenges posed to the entire nation by the Depression, the three major Negro League circuits weathered the storm and steadily built what was to become one of the largest and most successful black-owned enterprises in America. The existence and success of these leagues stood as a testament to the determination and resolve of black America to forge ahead in the face of racial segregation and social disadvantage.

To be continued

(Part 1 of 2 Parts)

Most everyone knows that Jackie Robinson was the first African-American to play major league baseball during the modern era. Surprisingly, few people have given much thought to how Robinson came to the attention of major league scouts, where he played before signing with the Dodgers, or just what the nature of baseball in the black community might have been before professional baseball's integration.

In the following paragraphs we'll take a quick trip through the years of baseball in black America that led up to Robinson's 1947 debut in Brooklyn. Our tour is intended to introduce those who are just learning about the Negro Leagues to this fascinating era in the history of American sports and society. There won't be much here to interest the baseball aficionado -- just a brief introduction for those newly discovering Negro League baseball.

1. The Baseball World Before 1890.

While it would be quite a stretch to say that professional baseball in the North was integrated between the end of the Civil War and 1890, quite a number of African-Americans played alongside white athletes on minor league and major league teams during the period. Although the original National Association of Base Ball Players, formed in 1867, had banned black athletes, by the late 1870s several African-American players were active on the rosters of white, minor league teams. Most of these players fell victim to regional prejudices and an unofficial color ban after brief stays with white teams, but some notable exceptions built long and solid careers in white professional baseball.

In 1884 the Stillwater, Minnesota club in the Northwestern league signed John W. "Bud" Fowler, an African-American with more than a decade's experience as an itinerate, professional player. Fowler, a second-baseman by preference, played virtually every position on the field for Stillwater, enhancing the reputation that had brought him to the attention of white team owners. Fowler's baseball career continued through the end of the 19th Century, much of it spent on the rosters of minor league clubs in organized baseball.

In 1883 former Oberlin College star Moses "Fleetwood" Walker began his professional career with Toledo in the Northwestern League. A more than average hitter, Walker was among baseball's finest catchers almost from the beginning of his career. When the Toledo club joined the American Association in 1884 Walker became the first black player to play with a major league franchise.

In 1886 both Walker and Fowler were in the white minor leagues along with two other black stars, George Stovey and Frank Grant. Doubtless, many other black players were playing with teams in the "outlaw" leagues and independent barnstorming clubs. At least in the North and Midwest the best black players found a measure of tolerance, if not acceptance, in white baseball until the end of the 1880s. But in 1890 this situation abruptly changed.

As the season of 1890 began there were no black players in the International League, the most prestigious of the minor league circuits. Without making a formal announcement, a gentlemen's agreement had been made which would bar black players from participation for the next fifty-five years. Though black players continued to find work in lesser leagues for a time, within only a few short years no team in organized baseball would accept black players. By the turn of the century the color barrier was firmly in place.

2. Professional Black Baseball Comes To The Fore

While Fowler, Walker, Grant and others were working to find a spot (and keep it) in organized baseball, other black players were pursuing careers with the more than 200 all-black independent teams that performed throughout the country from the early 1880s forward. Eastern teams like the powerful Cuban Giants, Cuban X Giants and Harrisburg Giants played both independently and in loosely organized leagues through the end of the century, and in the early 1900s professional black baseball began to blossom throughout America's heartland and even in the South.

The early years of the 20th Century saw an emergence of several powerful black clubs in the Midwest. Teams like the Chicago Giants, Indianapolis ABCs, St. Louis Giants and Kansas City Monarchs rose to prominence and presented a legitimate challenge to the claim of diamond supremacy made by Eastern clubs like the Lincoln Giants in New York, Brooklyn Royal Giants, Cuban Stars and Homestead (Pa.) Grays. In the South, black baseball was flourishing in Birmingham's industrial leagues, and teams like the Nashville Standard Giants and Birmingham Black Barons were establishing solid regional reputations.

By the end of World War I black baseball had become, perhaps, the number one entertainment attraction for urban black populations throughout the country. It was at that time that Andrew "Rube" Foster, owner of the Chicago American Giants and black baseball's most influential personality, determined that the time had arrived for a truly organized and stable Negro league. Under Foster's leadership in 1920 the Negro National League was born in Kansas City, fielding eight teams: Chicago American Giants, Chicago Giants, Cuban Stars, Dayton Marcos, Detroit Stars, Indianapolis ABCs, Kansas City Monarchs and St. Louis Giants.

In the same year Thomas T. Wilson, owner of the Nashville Elite Giants, organized the Negro Southern League with teams in Nashville, Atlanta, Birmingham, Memphis, Montgomery and New Orleans. Only three years later the Eastern Colored League was formed in 1923 featuring the Hilldale Club, Cuban Stars (East), Brooklyn Royal Giants, Bacharach Giants, Lincoln Giants and Baltimore Black Sox.

The Negro National League continued on a sound footing for most of the 1920s, ultimately succumbing to the financial pressures of the Great Depression and dissolving after the 1931 season. The second Negro National League, organized by Pittsburgh bar owner Gus Greenlee, quickly took up where Foster's league left off and became the dominant force in black baseball from 1933 through 1949. The Negro Southern League was in continuous operation from 1920 through the 1940s and held the position as black baseball's only operating major circuit for the 1931 season. In 1937 the Negro American League was launched, bringing into its fold the best clubs in the South and Midwest, and stood as the opposing circuit to Greenlee's Negro National League until the latter league disbanded after the 1949 season.

Despite the difficult economic challenges posed to the entire nation by the Depression, the three major Negro League circuits weathered the storm and steadily built what was to become one of the largest and most successful black-owned enterprises in America. The existence and success of these leagues stood as a testament to the determination and resolve of black America to forge ahead in the face of racial segregation and social disadvantage.

To be continued

Thursday, March 17, 2005

The Greatest Prison Baseball Player of All Time

Ralph “Blackie” Schwamb was the greatest prison baseball player of all time. “Wrong Side of the Wall” by Eric Stone is his story. In the late 1940s, at the same time as he was working his way up into the major leagues with the St. Louis Browns, Schwamb was working for gangsters in L.A. In 1949 he committed a murder while collecting on a debt for a bookie, was sentenced to life in prison and then put together a great career behind bars against surprisingly tough competition.

In San Quentin and Folsom prisons he pitched three no-hitters against teams made up almost entirely of major and high-level minor leaguers. He did that while backed up by a prison team with no professional experience, on fields that were very much hitters parks. He got out of prison in 1960, after 10 years, and nearly made a comeback when he signed by the Triple-A Hawaii Islanders of the Pacific Coast League.

Sports Illustrated' review

March 21st issue

The Best Behind Bars

It's hard not to groan at the subtitle of Los Angeles journalist Eric Stone's book The Wrong Side of the Wall: The Life of Blackie Schwamb, the Greatest Prison Baseball Player of All Time (Lyons Press, 310 pages, $21.95). Greatest prison baseball player? Is there no limit to baseball writers' appetite for minutiae? What next -- Isidor Lipschitz: King of the Borscht Belt Summer League?

But given that our nation has watched a parade of ballplayers from Darryl Strawberry to Ken Caminiti march to the beat of their own self-destruction, it's useful to remember that there's nothing terribly modern about the spectacle of an athlete throwing it all away. Schwamb was a gifted righthander who pitched only a dozen games for the St. Louis Browns before being jailed for the brutal murder of a Long Beach, Calif., doctor in 1949. He was also a legman for the notorious gangster Mickey Cohen. Stone, whose uncle played in a semipro league against Schwamb, hoped to discover "how someone [like Schwamb] with so much right in his life could go so utterly wrong."

Stone found the answer not in the rough-and-tumble world of the 1940s minor league circuit, which he vividly evokes, nor in the even rougher, more sordid world of organized crime in L.A. Rather, he discovered it in a broken-down old man he encountered living in a metal-slab-sided house in Lancaster, Calif. For four days Schwamb told Stone colorful yarns about his tragic, booze-soaked life. But on the fifth day, when Stone confronted Schwamb about the night he beat Dr. Donald Buge to death with his fists, Schwamb replied with a flood of tears. Then, collecting himself, he told Stone to "get the hell out of here before I [mess] you up." Clearly Blackie Schwamb was doomed to destruction for a simple reason: He couldn't find the courage to look at his reflection in the mirror.

Issue date: March 21, 2005

What do people think?

"Eric Stone's riveting account of Blackie Schwamb's great baseball talent and equally great character defects is so much more than a sports story. It is a fascinating trip along a life on the edge, in and out of trouble, golden opportunities and missed chances. Damon Runyon would have been proud to tell the tale of Blackie." —Tom Brokaw, longtime NBC anchorman and best selling author.

"Blackie Schwamb's story is classic tragedy--flawed, physically brilliant, unable to deal with his demons. This is not a "sports" story, it is Eric Stone's brilliant study of a flawed man with a great talent who had such a talent that he started against Bob Feller, went to The Mob and ended up pitching in prison leagues. Stone weaves the life of this tragic figure against the tapestry of the lifeline of both L.A.and The Mob. It is brilliant, chilling and real." —Peter Gammons, three-time National Sportscasters and Sportswriters Association National Sportswriter of the Year, ESPN Baseball Tonight studio analyst.

"Baseball rarely edges into noir, but this compelling biography by Eric Stone reads as if it had been filmed in black and white in the golden age of film noir Hollywood. Mesmerized by the waste of it all, yet tempted to hope because of his talent, we follow the story of a brilliant but flawed player, Blackie Schwamb, whose career was derailed through the tragic consequences of gangland connections." —Kevin Starr, University Professor in History, University of Southern California, California State Librarian Emeritus, author of "Coast of Dreams: California on the Edge, 1990-2003" and the other six volumes of the "Americans and the California Dream" series.

"Blackie Schwamb pitched in the American League for the St. Louis Browns. Blackie Schwamb pitched in Folsom and San Quentin... You’ll finish "Wrong Side of the Wall" asking yourself, ‘What if...’" —Joe Garagiola, former major league ballplayer, radio and television broadcaster, and bestselling author of "Baseball is a Funny Game."

"As a ten-year-old St. Louis Browns fan, I saw the apple-cheek side of baseball and loved it. Eric Stone’s look at the dark underside is eerie, fascinating, and impossible to put down." —Win Blevins, author of "Beauty for Ashes" and numerous other award winning historical fiction and non-fiction books.

For more info, seek Eric Stone's website at http://www.ericstone.com/

In San Quentin and Folsom prisons he pitched three no-hitters against teams made up almost entirely of major and high-level minor leaguers. He did that while backed up by a prison team with no professional experience, on fields that were very much hitters parks. He got out of prison in 1960, after 10 years, and nearly made a comeback when he signed by the Triple-A Hawaii Islanders of the Pacific Coast League.

Sports Illustrated' review

March 21st issue

The Best Behind Bars

It's hard not to groan at the subtitle of Los Angeles journalist Eric Stone's book The Wrong Side of the Wall: The Life of Blackie Schwamb, the Greatest Prison Baseball Player of All Time (Lyons Press, 310 pages, $21.95). Greatest prison baseball player? Is there no limit to baseball writers' appetite for minutiae? What next -- Isidor Lipschitz: King of the Borscht Belt Summer League?

But given that our nation has watched a parade of ballplayers from Darryl Strawberry to Ken Caminiti march to the beat of their own self-destruction, it's useful to remember that there's nothing terribly modern about the spectacle of an athlete throwing it all away. Schwamb was a gifted righthander who pitched only a dozen games for the St. Louis Browns before being jailed for the brutal murder of a Long Beach, Calif., doctor in 1949. He was also a legman for the notorious gangster Mickey Cohen. Stone, whose uncle played in a semipro league against Schwamb, hoped to discover "how someone [like Schwamb] with so much right in his life could go so utterly wrong."

Stone found the answer not in the rough-and-tumble world of the 1940s minor league circuit, which he vividly evokes, nor in the even rougher, more sordid world of organized crime in L.A. Rather, he discovered it in a broken-down old man he encountered living in a metal-slab-sided house in Lancaster, Calif. For four days Schwamb told Stone colorful yarns about his tragic, booze-soaked life. But on the fifth day, when Stone confronted Schwamb about the night he beat Dr. Donald Buge to death with his fists, Schwamb replied with a flood of tears. Then, collecting himself, he told Stone to "get the hell out of here before I [mess] you up." Clearly Blackie Schwamb was doomed to destruction for a simple reason: He couldn't find the courage to look at his reflection in the mirror.

Issue date: March 21, 2005

What do people think?

"Eric Stone's riveting account of Blackie Schwamb's great baseball talent and equally great character defects is so much more than a sports story. It is a fascinating trip along a life on the edge, in and out of trouble, golden opportunities and missed chances. Damon Runyon would have been proud to tell the tale of Blackie." —Tom Brokaw, longtime NBC anchorman and best selling author.

"Blackie Schwamb's story is classic tragedy--flawed, physically brilliant, unable to deal with his demons. This is not a "sports" story, it is Eric Stone's brilliant study of a flawed man with a great talent who had such a talent that he started against Bob Feller, went to The Mob and ended up pitching in prison leagues. Stone weaves the life of this tragic figure against the tapestry of the lifeline of both L.A.and The Mob. It is brilliant, chilling and real." —Peter Gammons, three-time National Sportscasters and Sportswriters Association National Sportswriter of the Year, ESPN Baseball Tonight studio analyst.

"Baseball rarely edges into noir, but this compelling biography by Eric Stone reads as if it had been filmed in black and white in the golden age of film noir Hollywood. Mesmerized by the waste of it all, yet tempted to hope because of his talent, we follow the story of a brilliant but flawed player, Blackie Schwamb, whose career was derailed through the tragic consequences of gangland connections." —Kevin Starr, University Professor in History, University of Southern California, California State Librarian Emeritus, author of "Coast of Dreams: California on the Edge, 1990-2003" and the other six volumes of the "Americans and the California Dream" series.

"Blackie Schwamb pitched in the American League for the St. Louis Browns. Blackie Schwamb pitched in Folsom and San Quentin... You’ll finish "Wrong Side of the Wall" asking yourself, ‘What if...’" —Joe Garagiola, former major league ballplayer, radio and television broadcaster, and bestselling author of "Baseball is a Funny Game."

"As a ten-year-old St. Louis Browns fan, I saw the apple-cheek side of baseball and loved it. Eric Stone’s look at the dark underside is eerie, fascinating, and impossible to put down." —Win Blevins, author of "Beauty for Ashes" and numerous other award winning historical fiction and non-fiction books.

For more info, seek Eric Stone's website at http://www.ericstone.com/

Wednesday, March 16, 2005

What Do You Know About Baseball?

Do you know the strike zone?

Write down the description of the official strike zone and check here for the answer:

http://mlb.com/NASApp/mlb/mlb/official_info/umpires/rules_interest.jsp

What are the ground rules for your favorite stadium?

Did you remember them all? Check here for the answer:

http://mlb.com/NASApp/mlb/mlb/official_info/umpires/ground_rules.jsp

You Make the Call archive

• With two out, the batter swings and misses at a pitch in the dirt. The pitch bounces off the catcher into the air, and the batter's bat strikes the ball, causing it to roll into foul territory. Get the ruling >

• In this play Paul Konerko hits a foul pop-up and is called out for batter interference. Get the ruling >

• A baserunner bumps into Travis Lee as he tries to catch a batter's pop-up. Is the call interference or obstruction ... or neither? Get the ruling >

• On Aug. 8, 2001 Johnny Damon hit a fair ball down the right field line which rolled -- and lodged solidly! -- into an empty beer cup lying on the field. Get the ruling >

• On May 8 in Arizona, the D-Backs' Damian Miller hits a grounder to the Reds' Pokey Reese, who attempts to beat Durazo to second base, but then decides to throw to first instead ... and airmails the throw into the seats. Get the ruling >

Fan Q & A archive

• Whatever happened to those balloon chest protectors? More >

• What's the funniest thing a manager has said during an argument? More >

• There are switch-hitters, but are there switch-pitchers? More >

• What are the causes for an Umpire to eject a player or a manager? More >

• I have only a vague idea what a balk is. What is the official definition? More >

• Can you tell me what the call was when Randy Johnson hit the birde with the ball (i.e. ball, dead ball, no pitch, or foul)? More >

There is a lot of baseball to learn, or even remember, at the official MLB website: http://mlb.mlb.com/NASApp/mlb/index.jsp

Write down the description of the official strike zone and check here for the answer:

http://mlb.com/NASApp/mlb/mlb/official_info/umpires/rules_interest.jsp

What are the ground rules for your favorite stadium?

Did you remember them all? Check here for the answer:

http://mlb.com/NASApp/mlb/mlb/official_info/umpires/ground_rules.jsp

You Make the Call archive

• With two out, the batter swings and misses at a pitch in the dirt. The pitch bounces off the catcher into the air, and the batter's bat strikes the ball, causing it to roll into foul territory. Get the ruling >

• In this play Paul Konerko hits a foul pop-up and is called out for batter interference. Get the ruling >

• A baserunner bumps into Travis Lee as he tries to catch a batter's pop-up. Is the call interference or obstruction ... or neither? Get the ruling >

• On Aug. 8, 2001 Johnny Damon hit a fair ball down the right field line which rolled -- and lodged solidly! -- into an empty beer cup lying on the field. Get the ruling >

• On May 8 in Arizona, the D-Backs' Damian Miller hits a grounder to the Reds' Pokey Reese, who attempts to beat Durazo to second base, but then decides to throw to first instead ... and airmails the throw into the seats. Get the ruling >

Fan Q & A archive

• Whatever happened to those balloon chest protectors? More >

• What's the funniest thing a manager has said during an argument? More >

• There are switch-hitters, but are there switch-pitchers? More >

• What are the causes for an Umpire to eject a player or a manager? More >

• I have only a vague idea what a balk is. What is the official definition? More >

• Can you tell me what the call was when Randy Johnson hit the birde with the ball (i.e. ball, dead ball, no pitch, or foul)? More >

There is a lot of baseball to learn, or even remember, at the official MLB website: http://mlb.mlb.com/NASApp/mlb/index.jsp

Thursday, March 10, 2005

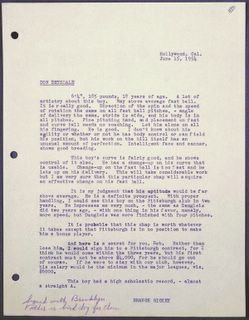

Casey Stengel Testimony

Baseball people testifying before congressional committee, does that sound familiar?

This week several high-profile baseball people were subpoenaed to testify before the House Energy and Commerce subcommittee on steroids. But this isn’t the first time baseball was asked to testify before a congressional committee.

On July 8, 1958, the Senate Anti-Trust and Monopoly Subcommittee asked both Casey Stengel and Mickey Mantle to testify about baseball’s anti-trust exemption. The subcommittee learned a lot that day, including a new type of communication called “Stengelese.” Casey certainly had a unique way of communicating.

Here is an excerpt:

Senator Langer: I want to know whether you intend to keep on monopolizing the world's championship in New York City.

Mr. Stengel: Well, I will tell you, I got a little concerned yesterday in the first three innings when I say the three players I had gotten rid of and I said when I lost nine what am I going to do and when I had a couple of my players. I thought so great of that did not do so good up to the sixth inning I was more confused but I finally had to go and call on a young man in Baltimore that we don't own and the Yankees don't own him, and he is going pretty good, and I would actually have to tell you that I think we are more the Greta Garbo type now from success.

Mickey Mantle gave a much shorter testimony, just nine words when he said to the sub-committee “My views are just about the same as Casey's."

Read the entire transcript, it is hilarious. The link above will take you there, courtesy of Baseball-Almanac.

This week several high-profile baseball people were subpoenaed to testify before the House Energy and Commerce subcommittee on steroids. But this isn’t the first time baseball was asked to testify before a congressional committee.

On July 8, 1958, the Senate Anti-Trust and Monopoly Subcommittee asked both Casey Stengel and Mickey Mantle to testify about baseball’s anti-trust exemption. The subcommittee learned a lot that day, including a new type of communication called “Stengelese.” Casey certainly had a unique way of communicating.

Here is an excerpt:

Senator Langer: I want to know whether you intend to keep on monopolizing the world's championship in New York City.

Mr. Stengel: Well, I will tell you, I got a little concerned yesterday in the first three innings when I say the three players I had gotten rid of and I said when I lost nine what am I going to do and when I had a couple of my players. I thought so great of that did not do so good up to the sixth inning I was more confused but I finally had to go and call on a young man in Baltimore that we don't own and the Yankees don't own him, and he is going pretty good, and I would actually have to tell you that I think we are more the Greta Garbo type now from success.

Mickey Mantle gave a much shorter testimony, just nine words when he said to the sub-committee “My views are just about the same as Casey's."

Read the entire transcript, it is hilarious. The link above will take you there, courtesy of Baseball-Almanac.

Sunday, March 06, 2005

"If They Get Hit, It’s Their Fault" - Don Drysdale

Hall of Fame pitcher Don Drysdale, who pitched 14 seasons for the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers, also broadcasted Angels’ games along with well-known announcer Dick Enberg. In Dick Enberg’s recent book “Oh My” published by Sports Publishing, LLC, Enberg talks about his relationship with Drysdale, during their six years together.

“On the mound, Don Drysdale was as imposing as hell. He was six foot six, and his size and wicked delivery - particularly when his long right arm came way of third base - made him one of the most feared pitchers of all time.”

“Off the field, however, he was as sweet as country honey. His laugh was as big as his sidearm breaking ball, and in the six years we shared the Angels broadcast booth, he not only made a bad day a good day, but also saved my sanity. I took games way too seriously.”

Dick describes how Drysdale was so competitive, that during broadcasts he would often become angry when one of the Angels players “did something stupid. In particular, he would get incensed when a batter took away the inside corner from an Angels pitchers by crowding the plate, and the pitcher failed to respond by throwing inside, instead offering what would prove to be a fat pitch on the outside part of the plate.”

“Damn it, the pitcher’s got to make a living too,” he would growl. “A fastball, a foot inside, is not a sin. If they get hit, it’s their fault. Get outta the way.”

In Drysdale’s career, he struck 154 batters. Although not a record, (Walter Johnson had 205 and Pink Hawley 201) Don does hold an honorable mention in this telling stat. He led the National League five times for most batters HBP (Hit By the Pitch) in one season. His highest single season mark was 20 in 1961.

Did Don ever hit someone intentionally? “They hit themselves, he would cry. They crowded the plate and stepped into an inside pitch and hit themselves. If you’re going to step into the pitch, I refuse to be held accountable. You’re taking money out of my pocket when you crowd home plate, he would say. I can’t let you do that. The inside part of the plate is mine too.”

One of Drysdale’s more memorable lines occurred once when his catcher signaled for an intentional walk and Don quipped, “Why waste four pitches when one will do?”

That was Don Drysdale.

“On the mound, Don Drysdale was as imposing as hell. He was six foot six, and his size and wicked delivery - particularly when his long right arm came way of third base - made him one of the most feared pitchers of all time.”

“Off the field, however, he was as sweet as country honey. His laugh was as big as his sidearm breaking ball, and in the six years we shared the Angels broadcast booth, he not only made a bad day a good day, but also saved my sanity. I took games way too seriously.”

Dick describes how Drysdale was so competitive, that during broadcasts he would often become angry when one of the Angels players “did something stupid. In particular, he would get incensed when a batter took away the inside corner from an Angels pitchers by crowding the plate, and the pitcher failed to respond by throwing inside, instead offering what would prove to be a fat pitch on the outside part of the plate.”

“Damn it, the pitcher’s got to make a living too,” he would growl. “A fastball, a foot inside, is not a sin. If they get hit, it’s their fault. Get outta the way.”

In Drysdale’s career, he struck 154 batters. Although not a record, (Walter Johnson had 205 and Pink Hawley 201) Don does hold an honorable mention in this telling stat. He led the National League five times for most batters HBP (Hit By the Pitch) in one season. His highest single season mark was 20 in 1961.

Did Don ever hit someone intentionally? “They hit themselves, he would cry. They crowded the plate and stepped into an inside pitch and hit themselves. If you’re going to step into the pitch, I refuse to be held accountable. You’re taking money out of my pocket when you crowd home plate, he would say. I can’t let you do that. The inside part of the plate is mine too.”

One of Drysdale’s more memorable lines occurred once when his catcher signaled for an intentional walk and Don quipped, “Why waste four pitches when one will do?”

That was Don Drysdale.

Tuesday, March 01, 2005

The Book of Unwritten Baseball Rules

The Book of Unwritten Baseball Rules by Baseball Digest (1986)

From The Baseball Almanac

In 1986, Baseball Digest published one of the absolute best lists to ever appear about the game of baseball. The Book of Unwritten Baseball Rules was a collaborative effort and is quite comprehensive. These are the rules that serious fans already know and new fans need to learn in order to speak baseball.

# Unwritten Rules

1 Never put the tying or go-ahead run on base.

2 Play for the tie at home, go for the victory on the road.

3 Don't hit and run with an 0-2 count.

4 Don't play the infield in early in the game.

5 Never make the first or third out at third.

6 Never steal when you're two or more runs down.

7 Don't steal when you're well ahead.

8 Don't steal third with two outs.

9 Don't bunt for a hit when you need a sacrifice.

10 Never throw behind the runner.

11 Left and right fielders concede everything to center fielder.

12 Never give up a home run on an 0-2 count.

13 Never let the score influence the way you manage.

14 Don't go against the percentages.

15 Take a strike when your club is behind in a ballgame.

16 Leadoff hitter must be a base stealer. Designated hitter must be a power hitter.

17 Never give an intentional walk if first base is occupied.

18 With runners in scoring position and first base open, walk the number eight hitter to get to the pitcher.

19 In rundown situations, always run the runner back toward the base from which he came.

20 If you play for one run, that's all you'll get.

21 Don't bunt with a power hitter up.

22 Don't take the bat out of your best hitter's hands by sacrificing in front of him.

23 Only use your bullpen stopper in late-inning situations.

24 Don't use your stopper in a tie game - only when you're ahead.

25 Hit behind the runner at first.

26 If one of your players gets knocked down by a pitch, retaliate.

27 Hit the ball where it's pitched.

28 A manager should remain detached from his players.

29 Never mention a no-hitter while it's in progress.

30 With a right-hander on the mound, don't walk a right-handed hitter to pitch to a left-handed hitter

From The Baseball Almanac

In 1986, Baseball Digest published one of the absolute best lists to ever appear about the game of baseball. The Book of Unwritten Baseball Rules was a collaborative effort and is quite comprehensive. These are the rules that serious fans already know and new fans need to learn in order to speak baseball.

# Unwritten Rules

1 Never put the tying or go-ahead run on base.

2 Play for the tie at home, go for the victory on the road.

3 Don't hit and run with an 0-2 count.

4 Don't play the infield in early in the game.

5 Never make the first or third out at third.

6 Never steal when you're two or more runs down.

7 Don't steal when you're well ahead.

8 Don't steal third with two outs.

9 Don't bunt for a hit when you need a sacrifice.

10 Never throw behind the runner.

11 Left and right fielders concede everything to center fielder.

12 Never give up a home run on an 0-2 count.

13 Never let the score influence the way you manage.

14 Don't go against the percentages.

15 Take a strike when your club is behind in a ballgame.

16 Leadoff hitter must be a base stealer. Designated hitter must be a power hitter.

17 Never give an intentional walk if first base is occupied.

18 With runners in scoring position and first base open, walk the number eight hitter to get to the pitcher.

19 In rundown situations, always run the runner back toward the base from which he came.

20 If you play for one run, that's all you'll get.

21 Don't bunt with a power hitter up.

22 Don't take the bat out of your best hitter's hands by sacrificing in front of him.

23 Only use your bullpen stopper in late-inning situations.

24 Don't use your stopper in a tie game - only when you're ahead.

25 Hit behind the runner at first.

26 If one of your players gets knocked down by a pitch, retaliate.

27 Hit the ball where it's pitched.

28 A manager should remain detached from his players.

29 Never mention a no-hitter while it's in progress.

30 With a right-hander on the mound, don't walk a right-handed hitter to pitch to a left-handed hitter

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)