Courtesy of BaseballReliquary.com

Exhibition: March 26-June 9, 2006

John F. Kennedy Memorial Library

California State University, Los Angeles

5151 State University Dr., Los Angeles, CA

Information: (323) 343-3953 or (626) 791-7647

The Baseball Reliquary, in collaboration with the John F. Kennedy Memorial Library, California State University, Los Angeles, will present the culmination of a year of scholarship in the form of an exhibition, Mexican-American Baseball in Los Angeles: From the Barrios to the Big Leagues, to be held from March 26-June 9, 2006. The exhibition, featuring artworks, artifacts, and photographs which document and interpret the historic role that baseball has played as a cohesive element and as a social and cultural force within the Mexican-American communities of the Los Angeles metropolitan area, will be in the display cases in the John F. Kennedy Memorial Library. The library is located on the campus of California State University, Los Angeles, 5151 State University Drive, Los Angeles, California. Library hours are Monday through Thursday, 8:00 AM-10:00 PM; Friday, 8:00 AM-5:00 PM; Saturday, 9:00 AM-7:00 PM; and Sunday, 10:00 AM-8:00 PM. For further information, phone the Baseball Reliquary at (626) 791-7647; for directions and parking information, phone the Office of the University Librarian at (323) 343-3953.

The exhibition is a component of a multi-faceted project, Mexican-American Baseball in Los Angeles: From the Barrios to the Big Leagues, which also includes the recording and preservation of oral histories and the establishment of an archive dedicated to Mexican-American baseball history as part of the John F. Kennedy Memorial Library’s Special Collections. This project is made possible, in part, by a grant to the Baseball Reliquary from the California Council for the Humanities as part of the Council’s statewide California Stories Initiative (http://www.californiastories.org/), and from the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles County Arts Commission.

GRAND OPENING RECEPTION:Sunday, March 26, 2:00 PM

The grand opening reception for the exhibition, Mexican-American Baseball in Los Angeles: From the Barrios to the Big Leagues, will be held on Sunday, March 26, from 2:00-4:00 PM, in the Courtyard of the John F. Kennedy Memorial Library on the Cal State L.A. campus. Refreshments will be served and the event is open to the public and free of charge. The reception will feature several speakers who will address various aspects of this comprehensive humanities-based project, including Cesar Caballero, Acting University Librarian, John F. Kennerdy Memorial Library; Francisco E. Balderrama, Professor of Chicano Studies and History, Cal State L.A.; and Richard Santillan, Professor Emeritus, Ethnic and Women’s Studies Department, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. Their remarks will be followed by a ribbon-cutting and first viewing of the library exhibition.

California State University, Los Angeles is located at the Eastern Ave. exit, San Bernardino (I-10) Freeway, at the interchange of the 10 and 710 Freeways. Public parking is available in Lot F or the top level of North Parking Structure II. A campus map can be viewed at www.calstatela.edu/univ/maps/cslamap.htm. For additional directions or parking information, phone the Office of the University Librarian at (323) 343-3953.

RELATED EVENT:Sunday, April 23, 2:00 PM

In conjunction with the exhibition, Mexican-American Baseball in Los Angeles: From the Barrios to the Big Leagues, Dr. Samuel Regalado, an advisor to the project and Professor of History, California State University, Stanislaus, will present a lecture entitled “Fernando Valenzuela and Beyond” and sign copies of his book Viva Baseball. This event, which is open to the public and free of charge, is sponsored by the Friends of the Cal State L.A. Library and will be held in the Martin Luther King, Jr. Building Lecture Hall II. For further information, directions, or parking instructions, phone the Office of the University Librarian at (323) 343-3953.

John F. Kennedy Memorial Library

California State University, Los Angeles

5151 State University Dr., Los Angeles, CA

Information: (323) 343-3953 or (626) 791-7647

The Baseball Reliquary, in collaboration with the John F. Kennedy Memorial Library, California State University, Los Angeles, will present the culmination of a year of scholarship in the form of an exhibition, Mexican-American Baseball in Los Angeles: From the Barrios to the Big Leagues, to be held from March 26-June 9, 2006. The exhibition, featuring artworks, artifacts, and photographs which document and interpret the historic role that baseball has played as a cohesive element and as a social and cultural force within the Mexican-American communities of the Los Angeles metropolitan area, will be in the display cases in the John F. Kennedy Memorial Library. The library is located on the campus of California State University, Los Angeles, 5151 State University Drive, Los Angeles, California. Library hours are Monday through Thursday, 8:00 AM-10:00 PM; Friday, 8:00 AM-5:00 PM; Saturday, 9:00 AM-7:00 PM; and Sunday, 10:00 AM-8:00 PM. For further information, phone the Baseball Reliquary at (626) 791-7647; for directions and parking information, phone the Office of the University Librarian at (323) 343-3953.

The exhibition is a component of a multi-faceted project, Mexican-American Baseball in Los Angeles: From the Barrios to the Big Leagues, which also includes the recording and preservation of oral histories and the establishment of an archive dedicated to Mexican-American baseball history as part of the John F. Kennedy Memorial Library’s Special Collections. This project is made possible, in part, by a grant to the Baseball Reliquary from the California Council for the Humanities as part of the Council’s statewide California Stories Initiative (http://www.californiastories.org/), and from the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles County Arts Commission.

GRAND OPENING RECEPTION:Sunday, March 26, 2:00 PM

The grand opening reception for the exhibition, Mexican-American Baseball in Los Angeles: From the Barrios to the Big Leagues, will be held on Sunday, March 26, from 2:00-4:00 PM, in the Courtyard of the John F. Kennedy Memorial Library on the Cal State L.A. campus. Refreshments will be served and the event is open to the public and free of charge. The reception will feature several speakers who will address various aspects of this comprehensive humanities-based project, including Cesar Caballero, Acting University Librarian, John F. Kennerdy Memorial Library; Francisco E. Balderrama, Professor of Chicano Studies and History, Cal State L.A.; and Richard Santillan, Professor Emeritus, Ethnic and Women’s Studies Department, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. Their remarks will be followed by a ribbon-cutting and first viewing of the library exhibition.

California State University, Los Angeles is located at the Eastern Ave. exit, San Bernardino (I-10) Freeway, at the interchange of the 10 and 710 Freeways. Public parking is available in Lot F or the top level of North Parking Structure II. A campus map can be viewed at www.calstatela.edu/univ/maps/cslamap.htm. For additional directions or parking information, phone the Office of the University Librarian at (323) 343-3953.

RELATED EVENT:Sunday, April 23, 2:00 PM

In conjunction with the exhibition, Mexican-American Baseball in Los Angeles: From the Barrios to the Big Leagues, Dr. Samuel Regalado, an advisor to the project and Professor of History, California State University, Stanislaus, will present a lecture entitled “Fernando Valenzuela and Beyond” and sign copies of his book Viva Baseball. This event, which is open to the public and free of charge, is sponsored by the Friends of the Cal State L.A. Library and will be held in the Martin Luther King, Jr. Building Lecture Hall II. For further information, directions, or parking instructions, phone the Office of the University Librarian at (323) 343-3953.

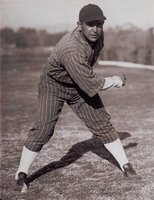

Pitcher Elias Baca, seen in this photograph ca. 1932, was the first Mexican-American baseball player at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Baca is one of many Mexican-American ballplayers highlighted in the exhibition, Mexican-American Baseball in Los Angeles: From the Barrios to the Big Leagues. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Reynaldo Baca.)

Courtesy of BaseballReliquary.com

Tom Lasorda (Allsport)

Tom Lasorda (Allsport)