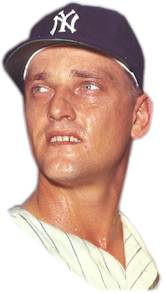

Roger Maris

At the

Baseball Hall of Fame Bullpen Theater on Friday, April 22 2005 and again on Sunday April 24, Andy Strasberg will present his story "Roger Maris and Me," a program on his friendship with Roger Maris and the Maris family.

Roger Maris and Me

by Andy Strasberg

I grew up in the shadow of Yankee Stadium and just fell in love with baseball. When Roger Maris came to the New York Yankees from the Kansas City Athletics in 1960, I was eleven. I had been burned in a fire in August, so I was laid up for a while and followed baseball even more closely. I remember a headline that said Roger Maris "rejuvenates" the Yankees. I had never heard the word before, but it made me think this Roger Maris was someone special. For me, there was something about the way he swung the bat, the way he played right field and the way he looked. I had an idol.

In 1961 the entire country was wrapped up in the home-run race between Maris and Mickey Mantle and Babe Ruth's ghost. I cut out every single article on Roger and told myself that when I got older and could afford it, I would have my scrapbooks professionally bound. (Eight years ago I had all of them bound into eleven volumes.) I usually sat in Section 31, Row 162-A, Seat 1 in Yankee Stadium. Right field. I would buy a general admission ticket, but I knew the policeman, so I would switch over to the reserved seats, and that one was frequently empty. I'd get to the stadium about two hours before it opened. I would see Roger park his car, and I would say hello and tell him what a big fan I was.

After a while, he started to notice me. One day he threw me a baseball during batting practice, and I was so stunned I couldn't lift my arms. Somebody else got the ball. So Roger spoke to Phil Linz, a utility infielder, and Linz came over, took a ball out of his pocket and said, "Put out your hand. This is from Roger Maris." After that, my friends kept pushing me: "Why don't you ask him for one of his home-run bats?" Finally, when Roger was standing by the fence, I made the request. He said, "Sure. Next time I break one." This was in 1965.

The Yankees had a West Coast trip, and I was listening to their game against the Los Angeles Angels on the radio late one night, in bed, with the lights out. And Roger cracked a bat. Next morning my high school friend called me, "Did you hear Roger cracked his bat? That's your bat." I said, "We'll see." When the club came back to town, my friend and I went to the stadium, and during batting practice Rog walked straight over to me and said, "I've got that bat for you." I said, "Oh, my God, I can't thank you enough."

Before the game, I went to the dugout. I stepped up to the great big policeman stationed there and poured my heart out: "You have to understand, please understand, Roger Maris told me to come here, I was supposed to pick up a bat, it's the most important thing, I wouldn't fool you, I'm not trying to pull the wool over your eyes, you gotta let me...." " No problem. Stand over here." He knew I was telling the truth.

I waited in the box-seat area to the left of the dugout, pacing and fidgeting. Then, just before game time, I couldn't stand it anymore. I hung over the rail and looked down the dimly lit ramp to the locker room, waiting for Rog to appear. When I saw him walking up the runway with a bat in his hand, I was so excited I almost fell. I don't know what he thought, seeing a kid hanging upside down, but when he handed me the bat, it was one of the most incredible moments in my young life. I brought the bat home, and my friends said, "Now why don't you ask him for one of his home-run baseballs?" So I asked Roger, and he said, "You're gonna have to catch one, 'cause I don't have any."

Maris was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals on December 8, 1966-a dark day for me. That year, I went off to college at the University of Akron, in Ohio. My roommate had a picture of Raquel Welch on his wall, and I had a picture of Roger Maris. Everyone knew I was a big Maris fan. My friends said, "You say you know Roger Maris. Let's just go see." So six of us drove two and one-half hours to Pittsburgh to see the Cardinals play the Pirates. It was May 9, 1967. We got to Forbes Field two hours before the game, and there was No. 9. It was the first time I had ever seen Roger Maris outside of Yankee Stadium, and I figured he wouldn't know me in this setting. I was very nervous. Extremely nervous, because I had five guys with me. I went down to the fence, and my voice quavered: "Ah,... Roger."

He turned and said, "Andy Strasberg, what the hell are you doing in Pittsburgh?" That was the first time I knew he knew my name. "Well, Rog, these guys from my college wanted to meet you, and I just wanted to say hello." The five of them paraded by and shook hands, and they couldn't believe it. I wished Rog good luck and he said, "Wait a minute. I want to give you an autograph on a National League ball." And he went into the dugout and got a ball and signed it. I put it in my pocket and felt like a million dollars.

In 1968, I flew to St. Louis to see Roger's last regular-season game. I got very emotional watching the proceedings at the end of the game. I was sitting behind the dugout, and Rog must have seen me because he later popped his head out and winked. It touched my heart. I was interviewed by the Sporting News, who found out I had made that trip from New York City expressly to see Roger retire. The reporter later asked Maris about me, and Roger said, "Andy Strasberg was probably my most faithful fan."

We started exchanging Christmas cards, and the relationship grew. I graduated from college and traveled the country looking for a job in baseball. When the San Diego Padres hired me, Roger wrote me a nice note of congratulations. I got married in 1976 at home plate at Jack Murphy Stadium in San Diego. Rog and his wife, Pat, sent us a wedding gift, and we talked on the phone once or twice a year. In 1980, Roger and Pat were in Los Angeles for the All-Star Game, and that night we went out for dinner-my wife Patti, me, my dad, Roger and Pat.

When Roger died of lymphatic cancer in December 1985, I attended the funeral in Fargo, North Dakota. After the ceremony, I went to Pat and told her how sorry I felt. She hugged me, and then turned to her six children. "I want to introduce someone really special. Kids, this is Andy Strasberg." And Roger Maris Jr. said, "You're Dad's number-one fan." There is a special relationship between fans-especially kids-and their heroes that can be almost mystical.

Like that time my five college buddies and I traveled to Pittsburgh to see Roger. It's so real to me even today, yet back then it seemed like a dream. I'm superstitious when it comes to baseball. That day I sat in Row 9, Seat 9, out in right field. In the sixth inning Roger came up to the plate and, moments later, connected solidly. We all-my friends and I-reacted instantly to the crack of the bat. You could tell it was a homer from the solid, clean sound, and then we saw the ball flying in a rising arc like a shot fired from a cannon. Suddenly everyone realized it was heading in our direction. We all leaped to our feet, screaming, jostling for position. But I saw everything as if in slow motion; the ball came towards me like a bird about to light on a branch.

I reached for it and it landed right in my hands. It's the most amazing thing that will ever happen in my life. This was Roger's first National League home run, and I caught the ball. Tears rolled down my face. Roger came running out at the end of the inning and said, "I can't believe it." I said, "You can't? I can't!" The chances of No. 9 hitting a home-run ball to Row 9, Seat 9 in right field on May 9, the only day I ever visited the ballpark, are almost infinitely remote. I can only explain it by saying it's magic-something that happens every so often between a fan and his hero. Something wonderful.

[AUTHOR'S NOTE: On August 3, 1990, I received a phone call from Roger's son Randy and his wife Fran. They were calling from a hospital in Gainesville, Florida. Fran had just given birth to their first son. Fran and Randy wanted me to know that they named their son Andrew and asked i f I would be his godfather. To this day I still can't believe that the grandson o f my childhood hero Roger Maris is my namesake and my godson.]

Andy Strasberg

For those who want to learn more about Roger Maris, please visit the official

Roger Maris website.