Sunday, May 29, 2005

Jose "Cheo" Cruz, #25

Tuesday, May 24, 2005

MLB: The true life story of baseballs

Sunday, May 22, 2005

By Mark Roth

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

As major league baseball games go, the Pirates-Brewers matchup May 13 had a fairly low BU.

BU stands for baseball usage, a statistic that was concocted entirely for this article.

It's a number that attempts to answer a simple question: How do 30 major league baseball teams manage to chew through the more than 900,000 5-ounce spheroids each season?

At a negotiated price of $72 a dozen, including taxes and shipping, the major league tab for baseballs comes to at least $5.5 million a year, which, to keep things in perspective, is less than the median salary of a New York Yankees player.

Still, numbers that big are hard to get a handle on, so it's easier to measure BU by the game.

In the May 13 contest, on a velvety cool Friday evening at PNC Park, the Pirates and Brewers used 104 balls, which is about 15 fewer than in a typical home game, according to Pirates equipment manager Roger Wilson.

That doesn't count the 14 to 15 dozen (168 to 180) baseballs Wilson sends out for batting practice for each home game.

For anyone who managed to last through a childhood summer with one baseball, even if it was wrapped in duct tape by the end, it may be baffling to wonder where all those baseballs go.

The top of the eighth inning in the May 13 game provided telling evidence. The game was tied 3-3, the Brewers were at bat, one batter reached base, no runs were scored, and yet the men on the field managed to use up 11 baseballs.

It started before the first pitch, when Pirates center fielder Jason Bay tossed his practice ball into the stands. It was one of four he personally donated to the fans that night, and one of 13 that players flipped into the seats, often to small boys with gloves bigger than their heads.

At one time, players could be fined for giving away balls, but the public relations value is now so universally accepted that no one says a word.

When play began, the first batter fouled off four balls; the next two batters fouled off two pitches; the umpire gave the catcher three more new balls to replace ones that hit the dirt; and, after the last batter popped out, Pirates catcher Humberto Cota kept the ball and tossed it to a fan.

After nine full innings of such disappearing acts, the BU for this tough 4-3 loss to the Brewers was:

Foul balls, 32

foul tips, 24

balls exchanged by the home plate umpire, 19

balls tossed into the stands by players, 13

balls carried off by fielders as their half inning ended, 8

balls exchanged at the pitcher's request, 4

home runs, 1

wild pitches, 1

and flukes, 2, once when an errant pitch hit Cota and once when Brewers catcher Chad Moeller plinked Daryle Ward's bat trying to throw the ball back to the pitcher.

As the breakdown suggests, home runs make up only a tiny fraction of the balls that leave the field of play.

Last season, major leaguers hit more than 5,400 homers, but that accounted for only one of every 120 balls that were consumed by the sport's voracious maw.

Equipment manager Wilson said that, each season, he orders 300 dozen baseballs a month and 750 dozen for spring training, which is more than 30,000 baseballs a year.

The balls arrive from Rawlings Sporting Goods in boxes, each one wrapped in tissue paper and stamped with the Major League Baseball logo and the signature of Commissioner Allan H. Selig, better known as Bud.

There used to be separate logos for the American and National Leagues, but now it's the same for everyone, just the way that umpiring crews now work in both leagues during a season.

The new balls look as if they've been buffed with tooth whitener, and they're slightly slick to the touch.

For each game, Wilson puts 14 or 15 dozen balls in a wire mesh basket for batting practice. The batting practice balls are either pristine balls right out of the box, or balls that have been used once in a game or once in a previous batting practice.

Ten or 11 dozen game balls go into a canvas bag after they've been "rubbed up" with a special mud that comes from one spot on the banks of the Delaware River in New Jersey.

The official story is that the umpires rub up these baseballs, but the job's actually done by a member of the home team's staff, usually the person who manages the umpires' equipment.

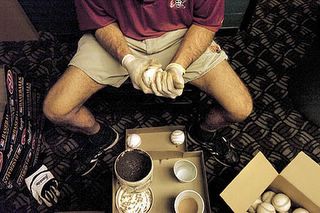

For the Pirates, that's John Bucci. He says one tin of the official Lena Blackburne Rubbing Mud will usually last him a season. Before each home game, he slips on hospital gloves so the grit and odor don't work their way into his hands, pours a judicious dollop of water onto the mud, and works it into the balls, occasionally spitting on them to get the right consistency.

Pam Panchak, Post-Gazette

Pam Panchak, Post-Gazette

John Bucci, the umpire attendent for the Pittsburgh Pirates, uses official Lena Blackburne Rubbing Mud to take the fresh-out-of-the-box white sheen off baseballs before a game.

Because the major leagues go through so many baseballs every season, the teams' equipment managers have worked out a barter system for road trips.

Wilson said the visiting team is responsible for providing its own batting practice and bullpen balls, but to avoid having to lug too many along on the plane, the home team will provide a case of balls -- six dozen -- for each game.

On a recent 10-game road trip to Houston, Arizona and San Francisco, that meant Wilson had to take 360 balls with him, and got the other 720 from the Astros, Diamondbacks and Giants. He returns the favor when those teams visit PNC Park.

With baseballs turning over faster than ballpark hot dogs, it stands to reason that the average life span of a baseball in the big leagues is brief.

These days, Wilson estimates, a ball lasts about eight days in the majors.

It is used only once in a game. Then it is relegated to batting practice, where it's used once or maybe twice, if it's not too beat up. From there it goes to the indoor batting cages under the stands for four or five days, and then Wilson ships it to one of the Pirates' minor league franchises, which will use it for practice until it's worn out.

Wilson does look for ways to extend the life of his baseballs.

He'll order as many dozen "blems," baseballs with slight flaws, as he can get from Rawlings for batting and fielding practice.

He has a dishwasher-size machine called a "renewer" which can add a few days of life to some balls if they're merely scuffed. The renewer is a tumbler filled with chunks of gum eraser, which helps remove some of the grass and dirt stains.

Baseballs account for the largest single equipment expense that Wilson makes for the Pirates.

And while baseball easily outdistances its pro sports' rivals -- football, basketball, soccer, hockey and golf -- in total BU, phone calls to the various leagues and sporting goods companies proved that competition is the one constant in American sports.

Virtually every league spokesman either guessed that his sport used more balls than any of the others, or if he could clearly see that wasn't the case, pleaded that each of his sport's balls was probably more expensive.

The only sport that came close?

It's tennis, which uses an estimated 875,380 balls per season for men's and women's pro tournaments, including practice and qualifying matches.

Article courtesy of Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Sunday, May 22, 2005

The Hidden Ball Trick

The hidden ball trick is one of those rare baseball morsels that comes and goes quickly, a glance in the wrong direction and you missed it. Many think it is extremely rare, but in fact, according to Retrosheet.org, there were 231 of these gems over the years, and several others that are unsubstantiated possibilities.

“It likely is baseball's most famous act of deception and trickery, which results in the victim being greatly embarrassed in addition to making an out. To pull it off, an infielder keeps the ball but tries to make it appear to a runner that he no longer has it. If the runner falls for it and wanders off the base, he is tagged out. The play was more common in the early days before rules were adopted that limited what the pitcher could do to make it appear that he had the ball when he did not. However, it is far from extinct as can be seen in the list below.”

The hidden ball trick confirms that a player wasn’t paying attention, was played the fool, is embarrassed in front of thousands, and laughed at on Baseball Tonight and Sportscenter.

Imagine getting tricked and making the last out in the game. There were eight instances of that happening, including Gary Carter on 4/8/1988. And it was Gary’s 34th birthday, no less. Vada Pinson was also victimized on his birthday, 8/11/1959 when he turned 21.

Two players had it happen three times: Ozzie Guillen (twice in 1989, 1991) and Jack Martin (1912, twice in 1914)

Three players were each fooled twice: Bill Dahlen (1902, 1906), Billy Werber (1937, 1940) and Birdie Cree (1910, 1913)

There must be some connection between a player’s name and his gullibility.

Victims include:

- A Buck (Ewing) and a Bucky (Harris), two Chicks (Fewster, Hafey), a Chief (Zimmer) and a Cupid (Childs).

- Three Docs (Cramer, Johnston, White), a Ducky (Holmes) and a Dusty (Baker).

- A Yost (Eddie), a Flick (Elmer), two Everetts (Booe, Scott), a Gabby (Street), and a Boots (Poffenberger)

- A Mickie (Cochrane) and a Minnie (Minoso), a Rabbit (Maranville), a Goose (Goslin) and a Ping (Bodie).

- A Stuffy (McInnis) and a Topsy (Hartsel), a Vada (Pinson) and Zoilo (Versalles)

- A Deacon (McGuire) and two Patsy’s (Dougherty and Gharrity)

What first name was the most common among victims?

- There were five Jimmys (Jimmie Foxx, Piersall, Sheckard, Slagle, and Wynn)

- Five Willies, (Davis, Horton, Keeler, Mays, Randolph)

- Seven Joes (Benz, Gedeon, Kelley, Keough, Quinn, Sargent, and Tinker)

- Eight Johns (Knight, O’Brien, Roseboro, Vander Meer, Bates, Butler, Evers, Mostil

Charlie Jamieson was the victim as part of a triple play on 4/30/1929, as was Chick Hafey on 9/6/1931.

Chief Zimmer was played the fool on opening day, 4/22/1897.

This famous threesome were also victims: Tinker (Joe), Evers (Johnny), Chance (Frank)

And Jimmy Slagle suffered the embarrassment in game two of the 1907 World Series.

The last one occurred on 9/15/2004 when third baseman Mike Lowell of the Florida Marlins fooled Brian Schneider of Montreal in the 4th inning.

Here is an exerpt from MarlinBaseball.com

MIAMI -- Falling under the heading -- You don't see this every day -- the Marlins successfully pulled off a hidden-ball trick against the Expos on Wednesday in Game 1 of a doubleheader at Pro Player Stadium.All-Star third baseman Mike Lowell caught the Expos napping, enabling the Marlins to pull off a sandlot play.To set the stage, the Expos went ahead 2-1 on Brian Schneider's double. With two outs in the fourth inning, Maicer Izturis was intentionally walked, bringing up pitcher John Patterson.Patterson lined a single to left field. Expos third base coach Manny Acta held Schneider at third, and left fielder Miguel Cabrera ran the ball in. Cabrera flipped the ball to shortstop Alex Gonzalez, who quickly tossed it to Lowell at third.By rule, the pitcher cannot be on the mound when the hidden-ball trick is executed. To keep the Expos off guard, Lowell trotted to pitcher Carl Pavano, and the play was on. In the confusion, the Expos never detected Pavano didn't have the ball.Lowell returned to third, and Pavano milled about the grass around the mound. When Schneider took a one-step lead, Lowell snapped a quick tag, and third base umpire Paul Emmel pumped out Schneider.

Ah yes, the glory of baseball.

Wednesday, May 18, 2005

Julio Franco

Julio Franco, venerable Atlanta Brave first baseman, will turn 47 this August. Since 1982, he has played in almost 2300 games with over 8200 at bats.

But, to me, the most amazing fact about his career is that, if you study who he has played with, it is a time machine. Just look at who were some of his teammates over the years:

Bert Blyleven

Charlie Hough

Bo Diaz

Steve Carlton

Tug McGraw

Mike Schmidt

Sparky Lyle

Gary Mathews

Pete Rose

Vern Ruhle

Mike Hargrove

Orel Hershiser

Phil Niekro

Tom Candiotti

Nolan Ryan

Pete Incaviglia

Rich 'Goose' Gossage

Jose Conseco

Ivan Rodriguez

Juan Gonzalez

By my unofficial count, Julio Franco has played with 547 different players (and against countless others) in his career and he's still going strong. He started in 1982, has played every year since except three, 1995, 1998 and 2000. In 1999 he only played in one game, one at bat and struck out.

Here is his profile, courtesy of baseballlibrary.com:

One of the most prolific hitters to emerge from the Dominican Republic, Julio Franco started out as one of the best offensive middle infielders of the 1980s, and gradually, due to a bad knee and weak fielding, switched over to the designated hitter position in the 1990s, thriving there as well.

Franco broke in with the Phillies in the early '80s, but didn't last long thanks to his multitudes of errors at shortstop. One of five players sent from Philadelphia to Cleveland for Von Hayes in 1982, Franco soon switched over to second base, thanks to the advice of his friend Manny Sanguillen. Some said the Dominican's immaturity made him a divisive presence during his six years with the Indians, but he was an easy target on losing teams with his weak defense and flamboyant style.

Hitting from a distinctive knock-kneed stance with his bat wrapped high behind his ear, he earned raves in 1985 when he drove in 90 runs, taking advantage of a very high 244 opportunities with runners in scoring position. Franco batted .303 or better in 1986-88, but the Indians continued to lose despite high expectations (one national magazine picked them to win the WS in 1987).

In his early years, Franco was considered a huge defensive liability, leading led AL shortstops in errors in 1984 and 1985, but as the years went on, he made fewer after his fielding percentage was used against him in arbitration hearings. His powerful bat only partly compensated for his lack of range, and he gained a reputation of being unable to make the big play defensively.

In May 1985 the Indians acquired shortstop Johnnie LeMaster and asked Franco to move to second base. Franco balked at taking the job from his friend Tony Bernazard, and LeMaster was sent packing three weeks later. Franco was finally moved to second base in 1988 after Corrales was fired and Bernazard was traded. Before the 1989 season, Franco was traded to Texas for Pete O'Brien, Jerry Browne, and Oddibe McDowell.

He soon emerged as a Rangers team leader and mentor to Rafael Palmeiro and Ruben Sierra. His first year in a Texas uniform, Franco hit .316 with 92 RBI and stole 21 bases in 24 attempts. In 1991, Franco notched his best year, tallying 108 runs, 201 hits, 15 dingers, 36 steals, and a league-leading .341 batting average. He also had a little post-season thrill that year, becoming an American citizen at the end of October. In December of that same eventful season, Franco found God, and became a devout Christian. Unfortunately, the following year, he missed all but 35 games due to a damaged right knee.

Speedwise, Franco never recovered, and was shifted to designated hitter and first base for good following his comeback. When the Rangers didn't resign him after the '93 season, Franco joined the Chicago White Sox, and immediately performed well: In the strike-shortened '94 campaign, Franco was on pace for his best offensive year, slamming twenty dingers before the strike and tallying 98 ribbies by mid-August. When the work stoppage began, Franco wisely packed up and headed for Japan, playing the 1995 season for the Chiba Lotte Marines; the next year, he was back in America, DH-ing and playing second for the Indians once again.

However, after a productive 1996 season, his numbers dropped and he was released in August of 1997. Milwaukee picked him up, and he finished the year with the Brewers before heading off for a second tour of duty with Chiba Lotte. In 1999, Franco played for Tampa Bay's Triple-A Mexico City affiliate, before getting called up to the majors for one at-bat (he struck out). On June 20th of that same year, fellow countryman Tony Fernandez surpassed Franco as the all-time hits leader for a player from the Dominican Republic.

Franco's seemingly dead career was revived for a last hurrah in 2001 by the Braves. Needing a first baseman for the stretch run, Atlanta signed the 40-year-old Franco out of the Mexican League on August 31st. In 25 games with the Braves, he batted .300 with three home runs and 11 RBIs. (JCA/AG/AGL)

[Editor's note: Julio Franco is still playing with the Atlanta Braves in 2005]

Tuesday, May 17, 2005

Charlie Muse, Former Pirates Executive & Batting Helmut Creator, Dies

May 16, 2005

PITTSBURGH (AP) -- Charlie Muse, a longtime Pittsburgh Pirates executive who created baseball's modern batting helmet, has died.

Muse died May 5 in Sun City Center, Fla., at age 87, the Pirates said. He had lived there since retiring in 1989 after 52 years with the team -- many as the traveling secretary. He was renowned with the Pirates for his honesty and thriftiness, often taking public transportation to the ballpark rather than more expensive taxis. He worked for the organization in a variety of roles, including ticket manager and head groundskeeper.

Muse was nicknamed "The Colonel'' because of his all-business approach, and it was his military-like ability to improvise that helped speed the invention of the batting helmet.

Until former Pirates general manager Branch Rickey pushed in the early 1950s for the creation of a protective helmet, batters traditionally wore only their cloth caps to the plate. At the time, Rickey owned American Baseball Cap Inc., and he chose Muse to run the company and design a suitable helmet.

"It (the development) was more difficult than people would think,'' Muse told The Associated Press in a 1989 interview. "The players laughed at the first helmets, called them miner's helmets. They said the only players who would wear them were sissies.''

Muse worked with inventor Ralph Davia and designer Ed Crick to perfect a helmet that was strong, light and aesthetically pleasing. They went through numerous designs before coming up with a comfortable plastic helmet that provided maximum protection above the ears, the most vulnerable area for batters.

Muse later had a prototype of the helmet molded into a lamp that sat on his office desk for years.

The Pirates were the first team to wear the helmets in 1952 and 1953, and their adoption was speeded after the Braves' Joe Adcock was beaned so severely by the Dodgers' Clem Labine on Aug. 1, 1954, that he was unconscious for 15 minutes.

Adcock said the helmet may have saved him from a severe injury, and the next day the Brooklyn Dodgers ordered all players in their organization to begin wearing helmets. Other teams quickly followed.

"There's no doubt about it, there was tremendous personal satisfaction from seeing the helmet become popular ... to see it save players from serious beanings,'' Muse said in 1989.

Muse was a minor league catcher and manager before and after serving as an Army captain in World War II and the Korean War, and occasionally donned catcher's gear even in his early 70s to catch spring training batting practice.

Sunday, May 15, 2005

Strike Out

by Matt Welch, National Post

July 13, 2002

Brooklyn Dodgers manager Leo Durocher, left, shakes hands with Jackie Robinson of the Montreal Royals before an exhibition game in Cuba on March 31, 1947.

Cuba produced many great Major League players in the 1960s and '70s, including Tony Perez who was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2000.

Jackie Robinson of the Montreal Royals looks over a roster of Brooklyn Dodgers players while training in Havana in 1947.

The U.S. Negro Leagues were stocked with Cubans such as Martin Dihigo a Hall of Famer in four countries.

George W. Bush would love to be the president who finally topples the Cuban dictator Fidel Castro. He would also probably not mind winning Florida by a somewhat more comfortable margin in 2004, or seeing his brother Jeb get re-elected governor this November.

With these goals as a backdrop, the Bush administration launched a crackdown last July on Americans who have the bad manners to spend money in Cuba -- 766 unlucky travellers were fined up to $7,500 for violating the Trading With the Enemy Act in 2001, up from just 188 during Bill Clinton's final year as president. By punishing a tiny fraction of the estimated 200,000-plus Americans who visit the communist island each year, Bush hopes to inflict indirect damage on the septuagenarian tyrant who has confounded no fewer than eight of his previous U.S. counterparts.

Which brings us to the revered Cuban baseball historian Severo Nieto. Nieto is certainly among the most peculiar and unsung victims of the long standoff between the United States and the Castro regime. While perhaps less spectacular and certainly less harrowing than many tales of repression emanating from Cuba, Nieto's story brings to light a sad and often unexamined effect not just of Castro's tyranny but of American policy: how the U.S. embargo has the effect of starving both sides of meaningful and important communication.

The apolitical Nieto, who is a few years older than El Jefe, basically invented Cuban baseball research in 1955 when he co-authored the country's first baseball encyclopedia, labouriously reconstructing the statistical record of the professional league's first 78 years out of a mountain of newspaper clippings, program scraps and his own scorecards. Since that debut, Nieto has been on one of the longest losing streaks in modern publishing history. He has spent a half-century documenting Cuba's tremendously rich professional past in more than a dozen books, but not a single one has been published in any country.

"I tried several times," Nieto told me in his cluttered Havana apartment four years ago, "but they say it's difficult now in Cuba because we don't have any paper."

Castro has been overseeing one of the world's most politically selective paper shortages for decades, reserving precious pulp for odes to Cuba's famed amateur athletic accomplishments while rejecting books that glorify anything about the pre-revolution era.

Cubans are not the only ones who suffer from this revisionist whitewashing. Americans want access to the archives, because the history of the two countries' professional baseball development is closely intertwined. Indeed, the story of the U.S. national pastime is inextricably linked to Cuba.

Long before Jackie Robinson broke the colour barrier (after the Dodgers' 1947 spring training in Havana, incidentally), Cuba was the only place where the best white major leaguers -- Ty Cobb, Christy Mathewson, Babe Ruth -- played against some of the top black talent of their era. The U.S. Negro Leagues were stocked with such Cubans as Martin Dihigo (a Hall of Famer in four separate countries) and black U.S. stars from Josh Gibson to James "Cool Papa" Bell and Buck Leonard, who spent their winters starring in the competitive winter league in Havana.

During the tumultuous 1950s, the Cuban Sugar Kings served as the AAA affiliate of the Cincinnati Reds in the summer, while winter-league fans could watch the likes of Brooks Robinson and Jim Bunning duke it out with Cuban stars Minnie Minoso and Camilo Pascual. U.S. scouts, led by Papa Joe Cambria of the woeful and heavily Cuban Washington Senators, fought over a talent pool that would produce many of the names that defined Major League Baseball in the 1960s and '70s -- Hall of Famer Tony Perez, three-time batting champion Tony Oliva, 1965 MVP Zoilo Versailles, three-time world champion Bert Campaneris, cigar-chomping pitcher Luis Tiant and 1969 Cy Young Award winner Mike Cuellar.

Even with a flurry of recent books about Cuban baseball, such as Roberto Gonzalez Echevarria's The Pride of Havana and Milton Jamail's Full Count, the historical record remains a gaping hole, one that Nieto is uniquely positioned to help fill.

"Very little information is available at this time. It's truly one of the last frontiers of baseball research," says Steve Wilson, senior editor of the McFarland & Co. publishing house, which bills itself as the largest publisher of serious baseball non-fiction. "Nieto's painstaking research over several decades has resulted in a tremendous store of information about this relatively unexplored area of baseball history."

The prospect of getting their hands on Nieto's unpublished treasure trove -- which includes such books as Big League Teams in Cuba, Martin Dihigo, El Maestro and Professional Baseball in Cuba, 1878-1961 -- has left American baseball historians salivating. Yet none of his work has ever seen the light of day across the Florida Straits. The main obstacle to the consummation has been a heartbreaking communications gap, created by two governments that have been unable to budge from positions of mutual hostility.

It's easy -- and not necessarily wrong -- to think of the U.S. embargo of Cuba primarily in economic and political terms: Washington hopes to starve Castro and his government to death, or at least to the point of collapse. But after 40 years, it's transparently clear that people such as Nieto are bearing the burden, impoverished as much by their removal from an international community of cultural and intellectual exchange as by their banishment from economic trade with the United States.

When I visited Nieto, his most prized possessions were not his various signed baseballs or ancient game programs, but rather letters from Americans expressing interest in his research. He proudly showed me carefully preserved correspondence from Jay Berman, a historian of the Pacific Coast League, and a number of historian-authors -- John Holway, Peter Bjarkman, Larry Lester -- as well as the publisher McFarland & Co. When I asked why these encouraging notes hadn't led to anything concrete, he shrugged and motioned to the telephone. "I can't call them," he said.

Most Cubans cannot make international telephone calls from their homes. Many can't receive them. Wilson of McFarland & Co. summarized the problem succinctly: "Mr. Nieto speaks no English and is, we are told, hard of hearing, so we have not tried to communicate by phone. Mail to and from Cuba is unreliable and e-mail non-existent."

In the end, the only real way for Nieto to communicate with his suitors and potential collaborators is for them to visit him in Cuba. That's especially unlikely to happen any time soon. The White House has plans to tighten the embargo.

Lawbreakers like me who go to Cuba are sent letters demanding the names and addresses of every place they slept and a full accounting of any money spent, upon penalty of prosecution. (In my case, I gave the authorities a very partial list and said that my non-American wife paid for all our expenses. After that, I never heard anything back.)

Havana is seething with Cubans trying to pump dollars from tourists. Walk through the central city as a blond man in a white T-shirt and you'll spend your days hearing the hissing "kss-kss!" sound of people trying to grab your attention. It isn't all about money scams, cheap cigars and prostitutes. Just as often --maybe more often -- the approaching strangers and instant friends just want to talk, to practise their foreign languages, to pepper you with questions about the outside world.

Who really killed Tupac? What are the lyrics to that Rage Against the Machine song and what do they mean? How are the people doing in Budapest and Prague now? Do American girls like Cuban men? Why does your country keep insisting on the bloqueo? How famous is Gloria Estefan? Why isn't Luis Tiant in the Hall of Fame? These are all questions I heard during my month there.

There are many things in Havana to be shocked by: the rotted buildings, the child prostitution, the high price of Cuban beer, the suffocating role of the state in virtually all human transactions. But the thing I found most appalling was the culture of information. Or, more precisely, the lack thereof.

The daily newspaper, Granma, is thin, horribly written, and used primarily for toilet paper (what with the shortages and all). The director of Cuba's sports Hall of Fame could not tell me how many members it had. It took me a week of asking dedicated baseball fans to find out how one could obtain a schedule for coming games. Periodical libraries -- filled with glorious back issues of Havana's handsome and competitive round-the-clock newspapers from before the Second World War -- are off-limits to most Cubans.

Though people are generally smart and jaded enough to tune out the government's propaganda, they don't have much of anything to replace it with, except for the odd BBC broadcast and contact with foreign tourists. Every conversation with an American about the United States undermines Fidel Castro by definition, because it surely contradicts the banal lies he and his media mouth on a daily basis.

For Nieto, you can see the visceral pleasure and national pride in his eyes when he meets someone who knows even a little about Cuba's baseball greats: such legendary players as the pitcher Dolf Luque, who passed for white and won 194 games in a 20-year Major League career with the Reds, Dodgers and Giants, and managed several of Cuba's most legendary teams; pitcher José Mendez ("El Diamante Negro"), who threw 25 shutout innings against visiting big-league teams in 1908; and Cocaina Garcia, a fat, little left-handed junkballer who starred both on the mound and in the outfield for decades.

Yet despite his joy at meeting like minds from the United States, Nieto has no way of knowing whether at least some of Castro's depictions of Americans as vicious capitalist sharks are true. Like several people who have met Nieto, I implored him to make me a copy of one of his books on a floppy disk (he has an ancient computer), so I could show it around to people at U.S. publishing houses. He clearly wanted to, but said that his son Eduardo, who lives in Spain, kept warning him about getting ripped off by greedy, back-stabbing Americans. At the end of our meeting, he finally agreed to have a relative of his bring me some disks on a coming trip to Los Angeles. I never heard from Nieto or his family again.

Other visitors tell similar stories. "Nieto had a friend who attended the Atlanta Olympics and I was supposed to meet him on the State House steps, but I was late because of traffic and missed him," said baseball historian John Holway, author of the Complete Book of Baseball's Negro Leagues. "I left messages for him at the press centre and wrote to Nieto to apologize, but he didn't answer."

Jay Berman, a retired California State University at Fullerton journalism professor and a charter member of the Pacific Coast League Historical Society, said he was finally able to bring back five of Nieto's disks a year ago, which he sent off to McFarland & Co., the baseball book publisher. "I think Nieto and his work could help finish up a lot of questions," Berman said. "But because he is 79 years old there's a very real question as to how much longer he's going to be able to.... That's part of the frustration of the whole thing."

McFarland & Co.'s Steve Wilson says that, after "several years of active, fruitful discussions with Mr. Nieto, primarily through intermediaries including his son," his publishing house is now "hopeful that a book may eventually result." No details are forthcoming, though the company plans to bring out two other major volumes on Cuban baseball history over the next two years.

For now, Nieto just continues to get older, while his historian colleagues in the United States become far more wary of travelling to Cuba because of Bush's policy of tightening the embargo yet again.

"I talked with a friend in Havana yesterday," Berman told me. "He says he's well aware of the crackdown and is suggesting to American friends that they stay away until after Jeb Bush is re-elected."

Does the diplomatic standoff leave any room for hope? Members of the Cuba Working Group say yes, they plan to reintroduce a bill overturning the travel ban this spring. Maybe a politician running against the Cuban American National Foundation will actually win a Florida election. Perhaps Severo Nieto's long-suppressed works will finally be published in the United States and in his native Cuba, to great acclaim --the literary equivalent of a last-chance, game-winning home run. But such moments are rare enough in baseball, let alone in life itself.

Thursday, May 12, 2005

Dontrelle Willis, Please Phone Home

May 11, 2005

By ROBERT ANDREW POWELL

ALAMEDA, Calif., May 4 - If Joyce Harris were to ever watch her son pitch, she would notice the same things everyone else does. His corkscrew windup. His enthusiasm. The boyish way he slaps his mitt after a strikeout, bounding toward the dugout without touching his cleats to the first-base line, his jaw working a wad of gum the size of a fish filet.

She would probably also notice the way her son, Dontrelle Willis, is maturing as a pitcher. Only 23 years old and in his second full season with the Florida Marlins, Willis has lowered his famously high leg kick, giving him a more consistent delivery. He no longer presses as much, either, which helps him work out of jams. Such growth has earned him a 6-0 record, including three complete games, a streak of 23 scoreless innings and a league-low earned run average of 1.07. He was named the National League pitcher of the month for April.

All of which might please Harris, 45, if she watched him pitch, which she does not. When Willis takes the mound for the Marlins, Harris lies in her bed here in an Oakland exurb, staring at the ceiling. Maybe she will turn on "Law & Order" or "Forensic Files." If she watches baseball at all, it will be a different game, no closer to her son than the scores crawling across the bottom of the screen. Friends call every inning with updates, knowing she is interested, knowing she is suffering.

"I can't watch him," she said. "I even can't listen to the announcers on TV say he's struggling or he's sweating or he's in trouble. When I look at him, I don't see a major league baseball player or an All-Star or a pitcher who won a World Series ring. When I look at him out there, I still see my 12-year-old boy, Dontrelle. And then all I want to do is protect him."

Willis and his mother have always been close. After the Marlins won the World Series in 2003, Harris weaved her son's initials into a rose tattoo blooming above her left breast. Willis refers to his mother as his hero. He keeps a framed picture of her on a shelf of his locker. In her honor he has inked her name onto the bill of his Marlins cap.

"We're almost too tight, almost like brother and sister instead of mother and son," Willis said. "Those things a mother might normally shield from her son she didn't keep from me, so we went through the struggles together."

But as he grows up professionally, he is growing into his own life.

In Willis's first year with the Marlins, Harris called him every day. Now they can go three days without speaking. Willis used to spend his off-seasons here, crashing at his mother's apartment. Now he lives at the Seminole Hard Rock Casino in Hollywood, Fla.

"I go back when I can, but my life is here now," he said. "My profession and my friends and all that."

Harris chooses to stay in Alameda. She likes walking to the Central Cinema, a funeral home turned into a first-run movie theater, stopping first at Forster's for a cone dipped in chocolate. She meets her gang at Peet's coffee, which they prefer over the Starbucks across the street. At least four times a week - usually more - she grazes the buffet at La Piñata Mexican restaurant. When the Marlins play the Giants, Harris rides the ferry across San Francisco Bay, pacing in the stands when her son pitches.

"She has her own life," said Sharon Peskett, her sister. "Even if Dontrelle doesn't play another day, she's still going to have her job. She takes classes. She has her speaking engagements. She's still his mother, no matter what, but she's letting him go."

Harris is known primarily as Dontrelle's mom, or Momma Willis or Mrs. Willis, even though she carries a different last name. Her identity is defined through her son much the way a military wife's is linked to her husband. When Willis made it to the majors in 2003 as a rookie sensation, Harris enjoyed the attention. At televised playoff games, she was shown wearing an engineer's cap in honor of her son's nickname, D-Train. On visits to Miami during baseball season, she would bounce from tailgate to tailgate in the stadium parking lot, posing for pictures.

"She enjoyed being on stage initially," said Frank Guy, her brother. "But people will put you on that stage because you're his mom. Like at the World Series, you could see that the cameras were about to focus on her, and then they did. She's not asking for that, and in time she learned that it's his stage and not hers."

She has her own stage, anyway. She is a journeyman ironworker, a welder of the Bay Bridge, the Kong roller coaster at Marine World and two of the gantry cranes that tower over Oakland Harbor. For the past year and a half, she has worked for the California Building Trades Council, acting as a sort of recruiter. She drives to schools and community centers across the Bay Area, talking up the benefits of union membership. Apprentice ironworkers earn as they learn, she said, making as much as $12 an hour to start, which is considerably more than they would be making at a fast-food restaurant. At meetings, she is often introduced as Dontrelle's mom.

"Which means I'll have to spend 10 minutes talking about my son, which isn't what I'm there to do," she said. "Now if they want to pull me over in the hall afterward to talk about him, that's fine, but I'm there to do a job."

Yet Harris still gives the D-Train tour of Alameda to anyone who asks. There is the mothballed aircraft carriers at the naval base. A plaque sticks to a concession stand in Rittler Park, behind Wood Middle School, where Willis got his start in Little League. On the mound of Willie Stargell Field at Encinal High, Willis evolved from a gangly freshman into the California player of the year; the No. 15 he wore is retired and hanging on the left-field tarp. There is the apartment they shared, where Harris still lives. Look closely at the red square painted on a wall in the parking lot. It is there that Willis debuted his leg kick while throwing tennis balls with neighborhood youngsters. When producers from HBO came out to film a segment on her son, Harris set out a plate of cranberry muffins.

"I do this because it's a part of my story, too, I guess," she said.

Willis's father left the scene soon after he was born, in Oakland, in 1982. For the first decade of her son's life, Harris struggled to keep steady work. The best job she held was as a part-time supervisor for United Parcel, working four days a week, taking home about $1,200 a month. Willis lived for seven years with his grandmother. Willis moved with Harris to Alameda when he was about 12, and Harris joined Ironworkers Local 378.

"She'd come to games here right off the Bay Bridge," Jim Saunders, Willis's high school baseball coach, said. "She'd be covered in so much dirt she looked like she'd been playing mud football or something."

Ironwork can leave people spent at the end of the work day. Harris still managed to attend almost all of her son's games. Working as a volunteer, Harris bent rebar to help build a skateboard park on the naval base. She molded a dance team from a handful of Encinal High girls. If her son stepped out of line in even a minor way, say by skipping class to get a haircut, she would be at the school at 3:30 p.m., in the baseball team dugout, asking why she got a call from the principal.

"She generally knew what he was doing at all times," Saunders said. "Honest to God, you never would have thought Dontrelle came from a one-parent family."

Willis made it to the majors in 2003, with the flat brim of his Marlins cap askew. His energy, along with a dazzling fastball, helped him win the rookie of the year award with a 14-6 record and helped the Marlins win a championship. Yet last season, the riddle of his windup appeared solved. Once opposing batters began hitting him, Willis tended to overthrow the ball, leading to more damage. His record fell to 10-11.

There are several reasons for his return to form this season. He stuck to a rigorous off-season conditioning program. A new pitching coach fine-tuned his delivery. To learn how to pace himself through a marathon season, he follows the examples set by the veteran Marlins, like pitcher Al Leiter and outfielder Jeff Conine.

"Some of this stuff you can only learn by experience," Willis said. "When to show up at the park, how to handle the fans, how to travel cross country, I'm doing everything a bit better."

He is better at acclimating to the life of a successful athlete. The day after he last pitched, against the Colorado Rockies, a clubhouse attendant pressed Willis's clothes for a party after the game. Jeffrey Loria, the Marlins' owner, ducked his head into Willis's locker to congratulate him on another victory, and to let him know there were Miami Heat playoff tickets waiting for him at the will-call window. Willis recently bought his mother a Ford Expedition, which she sent down to her sister, Sharon, who lives outside Los Angeles.

She has passed on gifts before. After Willis won the World Series two years ago, he gave Harris a bejeweled Marlins logo, to be worn around her neck. The back of the pendant was inscribed, "To Mom: I love you, Dontrelle."

Harris rarely wore the pendant, to her son's consternation. She felt it was too ostentatious. In the last year, though, as she has tried to build her life apart from Willis, she has started wearing it regularly.

"Even though I knew the day would come when he would move on with his life, I don't think as a mother you're ever prepared for it," she said. "It's taken some getting used to. He was my whole life."

Tuesday, May 10, 2005

A Diamond in the Rough: Iraqis Taking Up Baseball

By Ashraf Khali, Times Staff Writer

www.iraq.net

BAGHDAD — Yasser Abdel Hussein tugs his cap and unwinds with the smooth sidearm delivery that's made him the ace of the pitching staff. He looks like a prospect. At home plate, however, Mohammed Khaled seems like he's still on chilly terms with his bat as he crouches, resplendent in a red (yes, red) New York Yankees hat, FUBU muscle shirt and tight bicycle shorts. "It's a game of speed and concentration," Khaled says after widely missing most of Abdel Hussein's pitches. He connected just twice, and then only by abandoning all technique and swinging one-handed. The 20 young men gathered on a patchy grass field behind Baghdad University's College of Sports Education may not look like much now. But organizers of Iraq's fledgling national baseball team have high hopes.

As they work to introduce the sport to Iraqis who've never heard the phrase "home run," they're struggling with financial hardship, bare-bones equipment and a mortal fear that their fondness for this most American game will draw the wrath of the country's insurgency. Ismail Khalil Ismail, the founder of the 10-team league from which the national squad players are drawn, treads carefully to avoid the perception that his creation is a seed of cultural imperialism.

He dreads the thought of local newspapers "writing that we're playing an American game. But what game isn't American or British — basketball, soccer, boxing?" Ismail started his league last year with a few bags of donated equipment. He's desperate for material and financial support, but doesn't dare approach the U.S. Embassy or military. A U.S. Army unit recently invited the team to play against soldiers inside Baghdad's fortified Green Zone. "But we refused," said Bashar Salah, a muscular 24-year-old in a pinstriped jersey. "Not because of extremism, but to protect our lives."

Ismail first proposed the idea of bringing baseball to Iraq in 1996. The burly former national judo champion floated the idea to friends on the Iraqi Olympic Committee — then run by Saddam Hussein's son Uday. They quietly advised him to drop it, "because it was an American game and the Americans are our enemies." He revived the concept after the fall of the Hussein regime in April 2003. A friend from what Ismail would only describe as "an international charitable organization in Baghdad" arranged for a donation of a few balls, bats and gloves.

From there, Ismail started organizing on college campuses and at sports clubs. He held his first practice last October, and secured the support of the new Iraqi Olympic Committee this year. By summer, he had enough interest to organize a 10-team Baghdad championship tournament. Coaches then picked the best players to form the national squad. All receive a symbolic stipend of as much as $20 a month. For the players, the game is an intriguing novelty whose appeal transcends politics. "I was attracted by its newness — not because it's American, but because it's a new idea," Salah said. For now they practice regularly, and dream of traveling abroad to hone their skills.

Alaa Awad, a member of the baseball league's board of directors, said they didn't have the funding to consider trips to play against other national squads. "The only way we could accept an invitation was if the host country paid for us," he said. And "we can't really invite anyone to come here." There's also a shortage of regional competition.

In the Middle East, only Turkey, Iran, Morocco and Tunisia have national baseball teams. Officials from the Iraqi team wrote to counterpart organizations in Morocco and Tunis but haven't heard back. On a recent afternoon, the group — most of whom were abstaining from food and water during daylight hours for the Muslim holy month of Ramadan — gathered to run through hitting and pitching drills. Players took turns on the mound and at the plate, while assistant coach Ali Abdel Wahid stood behind the catcher and called out balls and strikes. The rest gathered haphazardly in the outfield, struggling to snare pop-ups and ground balls. Several players wore their batting helmets in the field. One wore his glove on his head.

Most of the players were obviously natural athletes, and the roster boasted several youth soccer stars and two members of the national team handball squad. But it was clear that picking up baseball skills would take time. When quizzed on their knowledge of the major league baseball playoffs, players could name only one team: the Yankees. Nobody could recall the name of a single player. "The hardest thing is teaching them while I'm learning myself," said Abdel Wahid, the assistant coach. He spends three hours a night researching rules and techniques online, and is translating the rule book, downloaded from the Major League Baseball website.

Once his players have the basics down, he looks forward to teaching them "to work together on the doubles play." Ismail acknowledges that he understood little about the game before launching his initiative. Mostly he just wanted to introduce a new sport to Iraq. "It was either [baseball] or rugby — I thought that would be good because Iraqis like violent sports like boxing or wrestling." But rugby would have required building goal posts, he said, whereas baseball can be played with a few bags of donated equipment.

Fearful of causing a backlash by advertising a Western connection, Ismail claims not to remember who sent the bats, balls and gloves. Some of the balls bear the name of the donor, but they're all too worn and smudged to make out much. On two balls, however, "Ogden, Utah" is legible. (Dano Jauregui, the baseball coach at Ogden-based Weber State University, said he had no idea about any kind of equipment donation to Iraq. Dave Baggott, the co-owner of the Ogden Raptors minor league baseball team, said he vaguely recalled some sort of equipment drive organized last year by a local civic group.)

From these humble beginnings, Ismail claims the sport's appeal is spreading. Teams have sprung up in the northern cities of Kirkuk, Irbil and Mosul. In Ramadi — in the fiercely anti-U.S. province of Al Anbar west of Baghdad — players practice with homemade bats and modified tennis balls, Ismail said. Inspired by the Iraqi soccer team's improbable fourth-place showing at the Athens Olympics, Ismail has high hopes. "We want to make this a success," he said. "We want to shock the world."

Monday, May 09, 2005

"I'll Be Back in Baseball After the War"

By Simon Kuper

Published: May 6 2005

Financial Times - ft.com

On April 20 1944, an American bomber flying over France was hit by German flak. Five of the six men aboard were killed, including the pilot, Elmer Gedeon.

Nobody would remember this except that Gedeon had played major league baseball for the Washington Senators. "I'll be back in baseball after the war," he had said on his last leave before going overseas.

The many histories of baseball at war invariably mention him and Harry O'Neill of the Philadelphia Athletics, killed at Iwo Jima. These men have become symbols of "baseball's sacrifice", the story of the national pastime rallying round when the US went to war - a story being retold for Sunday's 60th anniversary of VE Day. As baseball's hall of fame proclaims: "Ballplayers, like every other American citizen, understand the importance of giving one's self for their country."

In fact, ballplayers in the second world war didn't give themselves nearly as much as did other Americans. Nor did football players in Europe. Even then, celebrity athletes were protected. The less popular sports made the biggest sacrifices.

The reason Gedeon and O'Neill are always cited is that they were the only sometime major leaguers to die in the war. The statistics show that big-league baseball players had a relatively easy ride. In 1941 about 400 men were playing in the major leagues. Perhaps the same number of men of fighting age had recently done so. Let's say that there were therefore 800 current or recent major league players eligible to serve. If two of this group were killed, that makes 0.25 per cent.

In total about 405,000 Americans died in the war, the vast majority of them men aged 18 to 35. That means that about 1.8 per cent of the 22m American males in that age range were killed in the war. In short, a major league player had much less chance of "giving himself" than did "every other American citizen".

This is not because baseball players were cowards, or dodged service. More than 90 per cent of professional players in 1941 entered the army. Some asked for combat duty, but were denied it. In general, they survived because the army gave them protected posts. Baseball-mad officers recruited star players for their base teams, and weren't about to risk them being shot. For some time during the war the Great Lakes naval training centre outside Chicago had the world's best baseball team, regularly "whupping" major league teams.

The army was right to use ballplayers to play ball. A survey by the War Department had found that 75 per cent of servicemen enjoyed baseball or softball. Watching it surely helped soldiers' morale, and meeting ballplayers even more so: Thomas Barthel, a baseball historian, describes trips by baseball icons to places such as New Guinea or India, where their job was essentially to sit around talking to GIs all day.

The reason Gedeon and O'Neill were killed is that they were barely major leaguers at all. Gedeon's big-league career had spanned one week in 1939, while O'Neill's lasted just a game, in which he didn't bat. These men ended up in combat because nobody wanted to watch them play army ball. Only after their deaths did baseball claim them.

Footballers in Britain and Germany were favoured too, although more of them did die. Many English players became army PE instructors, spending the war playing football for various military teams. The great Tom Finney, shipped out to North Africa, told me he played so much that he left the army a much better footballer than he had entered it. In exhibition games late in the war, some of these stars were jeered by watching soldiers as "D-Day dodgers".

It was similar in Germany, where mothers of fallen soldiers began asking why the national football team was still playing. In late 1942 the team was disbanded - partly because it lost so often - and the players sent to the front. Two were killed almost immediately.

But mostly it was lesser athletes, or practitioners of obscure sports, who died in the war: for instance, about 50 minor league baseball players, dozens of rugby internationals, and an estimated 19 players from the US's then-obscure National Football League. Because these players were little known, they were sent into combat.

The greatest carnage of athletes, though, occurred in Hitler's camps. Dozens of Olympic and other athletes were gassed and then mostly forgotten. There is a heart-rending photograph of the Dutch female gymnasts who won a team gold at the 1928 Olympics. Of the 12 women pictured, four would die in Sobibor or Auschwitz.

In wartime, sports realise that they are frivolous and put out more flags. To this day they have managed to obscure which athletes died, and why.

Reproduced from ft.com

Wednesday, May 04, 2005

Play ball: British Columbia Teacher Helps Cuban Relive Glory

By TOM HAWTHORN

Tuesday, May 3, 2005

Special to The Globe and Mail

Ernest (Kit) Krieger, a Vancouver teacher, speaks un poco espagnol. Conrado (Connie) Marrero, a Havana retiree, speaks a leetle inglese. The language they share is baseball.

They both were once pitchers, although Mr. Krieger's professional career was so short as to be a sporting oddity. Mr. Marrero enjoyed great longevity on the mound, as in life. The oldest-living member of the old Washington Senators baseball team turned 94 last week, an event uncelebrated in the city where he once bamboozled opposing batters.

Major-league baseball returned to the United States capital this spring after a long hiatus. A parade of former players has been cheered by grateful fans. Mr. Marrero has not been among them.

Retired baseball players are a close-knit group who play games for charity, sign autographs for profit, and retell old stories for the sheer joy of it. Mr. Marrero lives in isolation from his baseball comrades, a hero in Cuba who is all but forgotten in a nearby land where many once marvelled at his pitching mastery. "He lives outside the fraternity, totally cut off from the world in which he once lived," Mr. Krieger said.

For seven years, Mr. Krieger has tried without success to integrate Mr. Marrero into the baseball community. His initiatives have been thwarted by a baseball establishment unable or unwilling to circumvent the U.S. Treasury Department's sanctions on trade with Cuba.

The old pitcher lives in a Spartan room in his grandson's walk-up apartment in Havana's Cerro neighbourhood. The walls are bare, betraying no hint of the celebrated past of one of Cuba's best pitchers in history. He does not receive a baseball pension.

The apartment is a long fly ball from the Estadio Latinoamerica, where he once earned the admiration -- and animosity, depending on club allegiance -- of his countrymen. Beneath the grandstand, his image has been painted on a wall, part of a mural that includes an image of Fidel Castro swinging a bat while dressed in green fatigues.

The Cuban leader is often wrongly described as having been scouted by the major leagues. He was more weekend warrior than serious prospect. After the revolution, he did pitch in exhibition games for a team called Los Barbudos (the Bearded Ones).

Mr. Castro shows little interest in the history of Cuban baseball before 1959, an era of low-paying contracts he dismisses as "slave baseball." So, it is left to Mr. Krieger and a handful of die-hard baseball fans to remind the world of the achievements of Mr. Marrero.

Conrado Eugenio Marrero Ramos was born to a poor sugarcane farmer in Sagua La Grande on April 25, 1911. His country roots earned him the nickname El Guajiro -- the Hillbilly. As an amateur, he was Cuba's greatest pitcher, a national hero in the 1940s known for a vast repertoire of pitches.

Listed wishfully as 5-foot-7, a measurement certainly taken while wearing spikes, he was a pudgy 158-pounder, looking little like an athlete, not the less for the ubiquitous presence of a fat cigar. However, he was blessed with a farmer's large hands, with long fingers the better to grip a baseball.

Mr. Marrero did not turn professional until age 35, then became a major-league rookie with Washington in 1950 at age 38. He celebrated his 39th birthday four days after his debut. He was called the "slow-ball senor," while his pitching motion was said to resemble "an orangutan heaving a 16-pound shot."

"Marrero's legs are so short that to batters he sometimes appears to be buried up to his waist on the mound," Life Magazine told readers in 1951. "He is so old that he creaks like an un-oiled windmill if he has to work more than once a week. He can throw a baseball just hard enough to reach the catcher. "Hitters who have been around the league a while have a contemptuous word for what he throws -- junk."

Mr. Marrero had the enviable ability to make batters look foolish. The great Ted Williams once said: "He throws you everything but the ball." The Cuban recorded 39 wins and 40 losses in five seasons with Washington, throwing at an age better suited to pitching horseshoes than baseballs.

He retired in 1954, returning to his homeland, where Mr. Krieger discovered him some 44 years later. The teacher found the player's name in the telephone directory. Mr. Marrero regaled the visitor with tales of meeting Connie Mack, of striking out Joe DiMaggio, of giving up a home run to Mr. Williams. "He is a shrewd, sharp, intelligent man," Mr. Krieger said. "If he lived anywhere else, he would be feted for his storytelling."

One baseball acquaintance the unlikely friends shared was Mickey Vernon, a team mate of Mr. Marrero's at Washington and the man who gave Mr. Krieger his big break in baseball.

In 1968, Mr. Krieger was a clubhouse attendant for Vancouver's minor-league team. The Mounties suffered from poor attendance. Mr. Krieger pitched a proposal to management -- let him pitch and he would fill the stands with his fellow university students.

Mounties manager Mickey Vernon agreed, and Mr. Krieger took to the mound to face the Hawaii Islanders on the final day of the season. The stands were empty as usual, but the clubhouse attendant fared better than feared. He surrendered just one run in three innings of work before being pulled from the game.

For the past four years, Mr. Krieger has included a visit with Mr. Marrero as part of his annual Cuba-ball Tours. The old player signs Topps cards and Senators caps in exchange for a few U.S. dollars. He has been presented with letters solicited by Mr. Krieger from Washington team mates, including third baseman Ed Yost, who wrote: "I caught many pop-ups that the batters hit from that great high slider of yours." Pitcher Sid Hudson sent $50.

Last year, Monte Irvin, a former Negro League player and a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame, made a pilgrimage to visit Mr. Marrero. The two had played together on Havana's legendary Almendares team in the late 1940s.

An embrace renewed a friendship in limbo for 55 years.

Connie Marrero

Sunday, May 01, 2005

Dave Dravecky - Cancer Survivor

The second was five days later in Montreal, Canada when a loud crack was heard in the stadium and Dave was suddenly lying on the mound writhing in pain from a broken arm. As Chuck Swindoll writes, “…he had delivered the pitch heard around the world.”

Dave’s victorious return to baseball is chronicled in his award-winning book, Comeback, which has sold more than 300,000 copies. Two months after he broke his arm in Montreal, Dave’s arm was broken again while celebrating the Giants’ National League Championship Series victory over the Chicago Cubs. The cancer had returned, and Dave retired from professional baseball in November 1989.

Additional surgeries and the recurring cancer finally led to the drastic amputation of Dave’s left arm, shoulder blade and left side of his collarbone. In the book, When You Can’t Come Back, Dave describes his loss. With the amputation of his arm, Dave Dravecky was stripped of his sense of identity and the worth he derived from it. He was propelled on a grueling journey to search for answers to questions every man must face: What gives a man identity and value? Is a man’s merit deeper than what he has and does?

Dave Dravecky is in great demand as a speaker, addressing a wide variety of audiences across the country. His messages range from motivational to inspirational to evangelical. Through his experience, he addresses loss and suffering, faith, encouragement and hope, reaching out to others and saying goodbye to the past. Hear the inspirational words of Dave Dravecky on overcoming adversity.