Sunday, May 22, 2005

By Mark Roth

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

As major league baseball games go, the Pirates-Brewers matchup May 13 had a fairly low BU.

BU stands for baseball usage, a statistic that was concocted entirely for this article.

It's a number that attempts to answer a simple question: How do 30 major league baseball teams manage to chew through the more than 900,000 5-ounce spheroids each season?

At a negotiated price of $72 a dozen, including taxes and shipping, the major league tab for baseballs comes to at least $5.5 million a year, which, to keep things in perspective, is less than the median salary of a New York Yankees player.

Still, numbers that big are hard to get a handle on, so it's easier to measure BU by the game.

In the May 13 contest, on a velvety cool Friday evening at PNC Park, the Pirates and Brewers used 104 balls, which is about 15 fewer than in a typical home game, according to Pirates equipment manager Roger Wilson.

That doesn't count the 14 to 15 dozen (168 to 180) baseballs Wilson sends out for batting practice for each home game.

For anyone who managed to last through a childhood summer with one baseball, even if it was wrapped in duct tape by the end, it may be baffling to wonder where all those baseballs go.

The top of the eighth inning in the May 13 game provided telling evidence. The game was tied 3-3, the Brewers were at bat, one batter reached base, no runs were scored, and yet the men on the field managed to use up 11 baseballs.

It started before the first pitch, when Pirates center fielder Jason Bay tossed his practice ball into the stands. It was one of four he personally donated to the fans that night, and one of 13 that players flipped into the seats, often to small boys with gloves bigger than their heads.

At one time, players could be fined for giving away balls, but the public relations value is now so universally accepted that no one says a word.

When play began, the first batter fouled off four balls; the next two batters fouled off two pitches; the umpire gave the catcher three more new balls to replace ones that hit the dirt; and, after the last batter popped out, Pirates catcher Humberto Cota kept the ball and tossed it to a fan.

After nine full innings of such disappearing acts, the BU for this tough 4-3 loss to the Brewers was:

Foul balls, 32

foul tips, 24

balls exchanged by the home plate umpire, 19

balls tossed into the stands by players, 13

balls carried off by fielders as their half inning ended, 8

balls exchanged at the pitcher's request, 4

home runs, 1

wild pitches, 1

and flukes, 2, once when an errant pitch hit Cota and once when Brewers catcher Chad Moeller plinked Daryle Ward's bat trying to throw the ball back to the pitcher.

As the breakdown suggests, home runs make up only a tiny fraction of the balls that leave the field of play.

Last season, major leaguers hit more than 5,400 homers, but that accounted for only one of every 120 balls that were consumed by the sport's voracious maw.

Equipment manager Wilson said that, each season, he orders 300 dozen baseballs a month and 750 dozen for spring training, which is more than 30,000 baseballs a year.

The balls arrive from Rawlings Sporting Goods in boxes, each one wrapped in tissue paper and stamped with the Major League Baseball logo and the signature of Commissioner Allan H. Selig, better known as Bud.

There used to be separate logos for the American and National Leagues, but now it's the same for everyone, just the way that umpiring crews now work in both leagues during a season.

The new balls look as if they've been buffed with tooth whitener, and they're slightly slick to the touch.

For each game, Wilson puts 14 or 15 dozen balls in a wire mesh basket for batting practice. The batting practice balls are either pristine balls right out of the box, or balls that have been used once in a game or once in a previous batting practice.

Ten or 11 dozen game balls go into a canvas bag after they've been "rubbed up" with a special mud that comes from one spot on the banks of the Delaware River in New Jersey.

The official story is that the umpires rub up these baseballs, but the job's actually done by a member of the home team's staff, usually the person who manages the umpires' equipment.

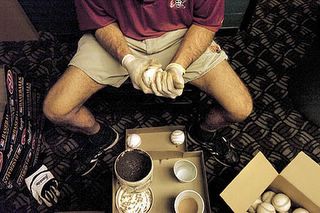

For the Pirates, that's John Bucci. He says one tin of the official Lena Blackburne Rubbing Mud will usually last him a season. Before each home game, he slips on hospital gloves so the grit and odor don't work their way into his hands, pours a judicious dollop of water onto the mud, and works it into the balls, occasionally spitting on them to get the right consistency.

Pam Panchak, Post-Gazette

Pam Panchak, Post-Gazette

John Bucci, the umpire attendent for the Pittsburgh Pirates, uses official Lena Blackburne Rubbing Mud to take the fresh-out-of-the-box white sheen off baseballs before a game.

Because the major leagues go through so many baseballs every season, the teams' equipment managers have worked out a barter system for road trips.

Wilson said the visiting team is responsible for providing its own batting practice and bullpen balls, but to avoid having to lug too many along on the plane, the home team will provide a case of balls -- six dozen -- for each game.

On a recent 10-game road trip to Houston, Arizona and San Francisco, that meant Wilson had to take 360 balls with him, and got the other 720 from the Astros, Diamondbacks and Giants. He returns the favor when those teams visit PNC Park.

With baseballs turning over faster than ballpark hot dogs, it stands to reason that the average life span of a baseball in the big leagues is brief.

These days, Wilson estimates, a ball lasts about eight days in the majors.

It is used only once in a game. Then it is relegated to batting practice, where it's used once or maybe twice, if it's not too beat up. From there it goes to the indoor batting cages under the stands for four or five days, and then Wilson ships it to one of the Pirates' minor league franchises, which will use it for practice until it's worn out.

Wilson does look for ways to extend the life of his baseballs.

He'll order as many dozen "blems," baseballs with slight flaws, as he can get from Rawlings for batting and fielding practice.

He has a dishwasher-size machine called a "renewer" which can add a few days of life to some balls if they're merely scuffed. The renewer is a tumbler filled with chunks of gum eraser, which helps remove some of the grass and dirt stains.

Baseballs account for the largest single equipment expense that Wilson makes for the Pirates.

And while baseball easily outdistances its pro sports' rivals -- football, basketball, soccer, hockey and golf -- in total BU, phone calls to the various leagues and sporting goods companies proved that competition is the one constant in American sports.

Virtually every league spokesman either guessed that his sport used more balls than any of the others, or if he could clearly see that wasn't the case, pleaded that each of his sport's balls was probably more expensive.

The only sport that came close?

It's tennis, which uses an estimated 875,380 balls per season for men's and women's pro tournaments, including practice and qualifying matches.

Article courtesy of Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

No comments:

Post a Comment